Dear Reader,

I have been quiet with this newsletter here for the last couple of months, because I have had a lot going on in another part of my life. A few weeks ago, I was appointed Interim President & CEO of The Trustees of Reservations, a splendid conservation and preservation organization in Massachusetts. I have been a hiker on Trustees properties and fan of its work for over 30 years and have had the great privilege of serving on its board for the last 15 years. Please be in touch and come visit! We have 123 properties to choose from.

Here I am on Day 2 of the new job at our All Staff Meeting with master gardener Dan Bouchard at Long Hill in Beverly, Massachusetts.

While this is all something of a surprise, it is a true honor to provide leadership to The Trustees for the next few months, and now that I have settled into this new role, I will be providing a briefer version of this newsletter in future issues. But for this week, I am offering a philosophical roundup of summer reading about, and—it’s hard to write this without a chuckle—the meaning of life!

One quick note. Since the last issue, I also published a review in Necessary Fiction of a lively, lockdown-inspired flash fiction collection: The Stairs Are a Snowcapped Mountain by UK writer Judy Darley. Darley’s trans-species speculations are quite companionable to the thoughts that follow in this issue.

The Trees and Me

I spent two weeks mostly alone in the Maine woods this summer, and emerged with senses roused and with a feeling of mystery. Was the forest one living thing or lots of things, some alive and some not alive?

As days went by, my ears began to interpret the sounds of the forest, for example the wind in the trees, with greater precision. The wind in the trees started to feel like a voice singing in different registers. Because I needed to harvest sunlight by relocating a solar panel across the clearing a few times throughout the day, my sense of time and light similarly sharpened. In the way that it moved, and in my interaction with it, I began to experience the light itself as if it was alive.

One morning when I heard branches across the river SNAP! in a particular way, I thought immediately: large mammal. And it was indeed, a bull moose. In one way, I was getting better at making distinctions among sensory phenomena; in another way, everything seemed to exist only in a constantly changing embrace with everything else.

I am not a student of philosophy, but today I find myself in need of it. To call the rocks, the dead tree trunks, the carpet of fallen pine needles I traversed every day alive would be both wrong and true. To call me an individual in that setting would be both true and wrong. Five books have been my recent companions in perplexity, and here are some notes on them in order of publication.

The Nature of Things

Lucretius

Translated by A.E. Stallings

Penguin Classics, 2015

433 pages

$22

Alicia Stallings’ buoyant, ingenious translation of De Rerum Natura brings a singular voice from the ancient world to life.

Lucretius wrote his Epicurean epic sometime around 60 B.C.E. to make the case that we live in an infinite cosmos made up of infinite atoms swerving into infinite combinations with each other. According to Lucretius, we may suffer in life, but there is no underworld or afterlife to worry about. Our consciousness comes to an end and our constituent parts are simply reabsorbed and rearranged into the universe. The poem is endlessly inventive (Virgil was a fan), and, clocking in at 7,500 hexameters, sometimes feels endless. The poem can be a bit contradictory (for a spirited argument against the idea of divine intervention, the gods make a lot of appearances), but, above all, Lucretius is full of appreciative and highly specific wonder at the panoply of creation and the astonishments of perception.

As if familiar with my diurnal dance at the cabin with my solar panels and the sun, he writes.

New rays of light are ever pouring forth, while old expire

Just like a thread of wool that’s being spun into a fire

Thus earth is easily despoiled of light and easily made

Full of light again, rinsing away the gloomy shade.

Lucretius makes the case that our sensory perceptions of the world is the first and most reliable source material in our search for truth. Stallings' translation is its own banquet of auditory delight.

The Spell of The Sensuous

David Abram

Knopf Doubleday, 1997

326 pages

$18

Having learned of it from the good folks at the magazine Emergence, I scored my copy of The Spell of the Sensuous for something like $3 at a used bookstore in Philly during AWP this year. David Abram is well known for having coined the term “the more-than-human world,” which is unwieldy but valuable. Abram is a philosopher, ecologist, world traveler, not to mention a practicing magician. These turn out to be excellent qualifications for his extended meditation on this question:

How is it that we have become so deaf and so blind to the vital existence of other species, and to the animate landscapes they inhabit, that we now so casually bring about their destruction?

Building on the work of philosophers such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and drawing on his study of indigenous cultures, Abrams explores at length the idea of reciprocity of relationships between the living and the non-living which, fusing their sensations and actions together, create a “collective landscape.”

If we dwell in the forest for many months or years . . . we may come to feel that we are a part of this forest, consanguineous with it, and that our experience of the forest is nothing other than the forest experiencing itself.

This is a buoyant text that I plan to return to again and again. Abrams offers us the promise of “loosening the psyche from its confinement within a strictly human sphere, freeing sentience to return to the sensible world that contains us,” and sparking a “rejuvenation of our carnal, sensorial empathy with the living land that sustains us.”

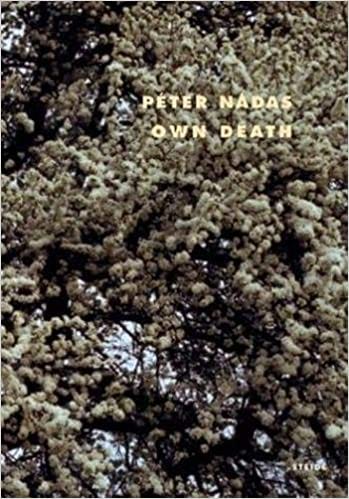

Own Death

Péter Nádas

Translated by Janos Solomon

Steidl, 2004

287 pages

Out of print

Over on Twitter, Luis Panini used the run-up to the annual awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature (Felicitations to Annie Ernaux!) to celebrate authors whose work he loves and believes would be worthy of the prize. Luis’ feed has become a capacious, occasionally raucous, celebration introducing me to many writers. One such discovery is the Hungarian novelist Péter Nádas.

Luis’ post prompted me immediately to learn more.

Own Death is sui generis, a visionary autofictional novella told in spare fragments The narrator recounts his experience of having a heart attack, experiencing what is called clinical death, and being brought back to life by a medical team in a hospital. What makes the book lushly peculiar is the interweaving of the story with over one hundred photographs of a single wild pear tree in the author’s garden made in all four seasons. The images of the tree, which is almost certainly older than the narrator, and will likely outlive him, create a kind of very heavy counterweight to the story, so that the story of the dying man seems to float as a (minor?) episode within the life of the tree. The prose is philosophical, ornamented with sharp detail and twists of irony and dark humor and a constant push toward the ultimate.

I was moving out, not by an attraction or promise, but by the power of Creation. Totality does indeed realize itself in you. It carried me. Not away from my consciousness, as in fainting, but into it. What seized me was an enormous force that operates simultaneously within and without, and therefore it is pointless for consciousness to make such a distinction. We were beyond everything personal and passionate.

While difficult to get hold of (I was able to borrow it from the Boston Athenaeum) this is a physically gorgeous book and well worth seeking out via Interlibrary Loan. Both the text and the photos are suffused with endless varieties of light, which, mixed with a gleeful undertone of absurdity, leave the reader with a sense of triumph.

Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things

Jane Bennett

Duke University Press, 2010

200 pages

$24.95

The Zen priest and novelist Ruth Ozeki recommended Vibrant Matter during her recent interview on the Ezra Klein Show podcast. She said,

And I’m thinking about Jane Bennett’s book Vibrant Matter, this idea that matter has agency, that things, the nonhuman forces have agency and effect on the planet. I certainly think that with climate change upon us, we really need to radically reconceive our relationship with matter and the material world. We need to take trees seriously, right?

Right!

I downloaded Vibrant Matter to my e-reader immediately. Jane Bennett is a political philosopher at John Hopkins University. Despite Ruth Ozeki’s comment, there isn’t much about trees in Vibrant Matter. This is a more technical treatise than The Spell of the Sensuous, but for a work of academic philosophy the writing is spirited.

Bennett proposes a construct she calls vital materialism. She seeks to shift our characterization of inanimate objects like metals and forces like wind from “passive . . . raw, brute, inert” to “lively” (if not alive). Things are co-participants with humans in complex, powerful assemblages like power grids, or the microbiomes in our guts. She works to “gnaw away at the life/matter binary.” She wants to “horizontalize the relations between humans, biota, and abiota.”

Bennett also mounts a defense of oft-criticized anthropomorphism, which she sees as an act of solidarity with the rest of the universe that can help break down the pervasive construct of humans as masters of the earth with a monopoly on powers like language and judgment (see Frugal Chariot 30). “An anthropomorphic element in perception can uncover a whole world of resonances and resemblances—sounds and sights that echo and bounce far more than would be possible were the universe to have a hierarchical structure.”

The most important part of Bennett’s argument has to do with how non-human elements of our world might be somehow represented in human political processes. Alas, there is no reference in the book to historical movements like the development of the land conservation movement, the passage of The Clean Air Act of 1970 or the Montreal Protocol (see Frugal Chariot Issue 23) or laws that govern matters such as animal welfare or wetlands protection, so I found her discussion of environmental political action incomplete and abstract. I suspect some critics on the left might lose patience with her lack of deep engagement with the way capitalism works to avoid accountability for environmental harm.

I do think Bennett makes a good point that democracies, which have been on a path of including groups of humans who had previously been excluded, could extend those protections more systematically or more forcefully to our ecosystems. It seems possible to me, for example, that the rising frequency and severity of drought will cause humans to grant more rights or protections to rivers in the future, but whether such rights will arise from some new paradigm of human enlightenment or the typical human instinct of last-minute self-preservation is, indeed, an open question. That they will come too late to prevent severe stress and extinction events seems, alas, likely.

How I Became a Tree

Sumana Roy

Yale University Press, 2021

248 pages

$16.00

A book that urges you to go ahead and think openly what you have been secretly thinking, to step forward into life with more honesty and a renewed sense of the possible, is a book to treasure.

. . . when I look back at the reasons for my disaffection with being human, and my desire to become a tree, I can see that at root lay the feeling that I was being bulldozed by time.

“My disaffection with being human.” This phrase yanked hard on my ponytail. For most of my life, I have proceeded on the belief that the vast majority of people are good-hearted and are trying to do their best. I still believe this, however it no longer serves as the consolation it used to as I watch humanity’s failures as we systematically degrade that which sustains us. Sumana Roy’s contemplative yet urgent essays in How I Became a Tree take the reader on a tour of her, and our, spiritual crisis in search of answers in the plant kingdom.

Roy, who is also a poet and novelist, teaches at Ashoka University in India, and this book is rooted in the Bengal landscape she loves so much. This series of episodes in her move to tree-ishness are recounted with a sparkling mix of personal honesty, devotion to history and a mischievous spirit of inquiry that brings to mind writers like Montaigne, Orwell and Solnit.

“To live in a forest is therefore to get lost in a forest, voluntarily and without regret.”

There is value in giving ourselves up to the world in new ways right now, to let go of some of the boundaries and categories we use for shorthand, to thinking about life and time in new ways. All of these books helped me do this, but nothing, absolutely nothing has done it so much as spending time with trees. I wish you all lots of tree time and the freedom to get a little lost as we approach the solstice.

Thank you for supporting me in this new role and in a shorter format for the months to come. And please chime in with your favorite books on trees and on the meaning of life.

Sincerely,

Nicie

An author who changed my thinking about life and time ever since I first discovered his work in a used bookstore some years ago is the archaeologist-author Loren Eiseley. His first book, The Immense Journey, came out in 1957. Questions about evolution, ecology, & the human place in it all are woven throughout his writings. This page has a good list of quotes people have pulled from his books: https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/56782.Loren_Eiseley