Dear Reader,

I hope that this (news)letter finds you well and settling into September rhythms, wherever you are.

We are just back from sailing on the Maine coast. Going to sea in a small boat requires constant vigilance, and some of that vigilance goes into resource management. We have two main water storage tanks, and we pump water by hand into the sinks. We have learned to wash dishes with the smallest amount of water possible. We use the tiniest dribbles from the faucet to rinse cutlery. We can make each tank last about six days if we are careful. When I go ashore after time on the boat, I have to stop myself from constantly turning off the tap between scrubs for the first couple of days.

Our boat has no refrigeration equipment. We have an icebox. We load six ten-pound blocks into the icebox, stow our most perishable items, and then cover all with a shower of cubes—fifteen pounds of them. Though the icebox works well in the moderate summer temperatures that generally prevail in Maine, melting accelerates on days over eighty degrees. And the nights are getting warmer too.

In late August of this year, for the first time in twenty-five seasons of Maine sailing, it was so hot when we we headed out that we brought two coolers on board to store extra blocks of ice. Our limiting resource this summer wasn’t food, fuel, or water. What required us to leave the quiet and remote coves we treasure, and visit harbors with services, was the need for ice.

As for our bodies, we cool and warm them mainly by using layers of clothing, swimming when it’s hot, and making a little fire in our wee wood stove to take the edge off a cold morning. We kindled only two or three fires this summer, and we did a LOT of swimming.

I had all this in mind as I read Eric Dean Wilson’s timely new book After Cooling, grateful for the privilege of reading it in the shady comfort of my bunk.

On to this week’s issue. But first, a note of truly heartfelt thanks to YOU, dear reader, as we celebrate the six-month anniversary of this little donkey cart. For those of you who haven’t yet become paid subscribers, here’s your chance to clamber aboard and support Frugal Chariot.

Review

After Cooling: On Freon, Global Warming, and the Terrible Cost of Comfort

Eric Dean Wilson

Simon & Schuster, 2021

480 pages

$28.00

I have a snapshot memory of my dad’s left arm as seen from the back seat of his 1965 Buick Special, as we sped north from Washington DC for summer vacations in the early 70s. While he steered with his right hand, he rested that left arm on the top of the driver’s door, toasting his skin to a reddish brown. The arm was strong, relaxed. We were on our way. There was no air conditioning in our car, so to deal with heat we ran the fan and kept those windows rolled down, most or all of the way.

We didn’t have air conditioning in our DC home either, so on hot days we sat on the porch, hoping for a thunderstorm. We watched the dark clouds like previews before a movie, enjoyed the show, and applauded the cooler air that followed. There was often iced tea with lemon and sugar, and long spoons to stir the tea until the grains of sugar dissolved. We were hot and sweaty, but we were comfortable enough. Then again, days over 95 were pretty rare in Washington back then. Not so much any more.

What happened to open windows and front porches? According to Eric Dean Wilson, in his thoughtful new book After Cooling: On Freon, Global Warming, and the Terrible Cost of Comfort, the symbiotic relationship between the suburban subdivision and central air conditioning caused real estate developers to eliminate porches, and prompted families (especially in the South) to close their windows and blast the AC. The cost to the ways in which neighborhoods feel and function has been significant. The cost to the ozone layer was nearly fatal. These days I am constantly thinking about the relationship of the ways we live our individual lives to the systemic forces causing global environmental degradation. So I was truly eager to read a focused history of air conditioning, a technology which humans as a species will certainly need more of in the future—but which we might at the same time consider using less if we don’t really need it. As Wilson explains,

Refrigerant punctures the narrative we Americans tell ourselves, the myth of the closed system—that we can live isolated from others, that we can promise a world of safety, that our actions in pursuit of a certain idea of comfort have no effect outside our borders, and that we are not so vulnerable to each other or reliant on one another.

The story of air conditioning is indeed worthy of contemplation. First, because it is a fraught case study in the history of the American workplace and the hidden costs of the middle-class lifestyle. Second, because it led to the only extant example of numerous countries coming together to make a binding agreement to ban the production of a major global pollutant. The Montreal Protocols of 1987 created an iterative framework for phasing out the use of CFCs—of which Freon is the best known—after scientists proved that CFCs were destroying the tissue-thin ozone layer that protects life on earth from the destructive power of UV solar radiation. The agreement worked, even though ozone depletion has been healing only gradually over the decades. Third, air conditioning is important for the humans of the future. With global warming and continued GDP growth in the Global South, cooling—already 20% of global electricity demand in buildings—is slated to drive 40% of the growth in demand for electricity globally over the next thirty years, according to an IEA study titled The Future of Cooling. In parts of the US, cooling already comprises 70% of peak power demand, a critical metric as we move to renewable generation, which will require storage mechanisms to manage peak loads on the grid.

Eric Dean Wilson is a writer based in New York. He is working toward a Ph.D. at the CUNY Graduate Center, through which he also teaches at Queens College, with a focus on environmental justice and climate change. This ambitious book, from a writer of great promise, combines not only multiple stories but also multiple modes, and leaves the reader with much to ponder. Of late I have noted what seems to be the now-prevailing model for narrative nonfiction climate books. Personal story-telling—often with a slightly picaresque, hipster vibe—is blended with a mixture of historical narrative, scientific explanation, and policy discussion. Wilson employs all these elements, and he also writes as a cultural critic with a philosophical bent and deeply held views about the rapacious and dangerous nature of capitalism. All this is a lot to manage, and results in a long and discursive book.

The story of Wilson’s friend Sam, which runs through the book, is the most compelling thread. Wilson rides along with Sam, who is a player in the active market for leftover Freon and other CFC gases. Using online detective work and old-fashioned calling around, Sam locates relatively small tanks of CFCs and negotiates their purchase, in order that his company can destroy the gases and sell the resultant carbon credits at a profit under California’s cap-and-trade regime. Many of the people who own these tanks are gearheads of some description, often working on old cars. Sam’s interactions with these folks, mostly white men in rural America, are colorful—and at times profound.

Also engaging are the historical portraits of the larger-than-life, pretty-much-crazy inventor entrepreneurs who created the technical foundations and business case for mechanical cooling, and left a complex legacy of innovation and pollution. How perfectly American that the earliest successes for the new technology were at the New York Stock Exchange and in movie theaters selling escapism during the Depression. Wilson explores the way cooling was pushed by the nascent industry into schools, workplaces, and homes—and the unsuccessful resistance from fresh-air believers. He also describes the long and difficult scientific and political process that resulted in the Montreal Protocols (spoiler: industry players led by DuPont fought it until they realized it promised a replacement cycle).

The author makes a strong case that AC is a key component in a technological cocoon of “comfort” that can isolate us and exacerbate our inequities and divides. At the same time, he shows how affordable access to electricity and cooling is an environmental justice issue. Indeed, AC’s function of managing temperature and humidity will be increasingly essential in a future with more frequent wet-bulb temperatures over 35 degrees celsius, which will make it life-threatening to go outside during heat waves for the 3 billion people who live in tropical regions.

After Cooling lost me in places. Technology and capitalism receive a good deal of blanket condemnation. Even noise-cancelling headphones, which use trivial amounts of electricity and alleviate suffering for many people with auditory conditions, come in for scorn. There is much heartfelt moral anguish in this book, but it seems muddled at times. One senses a disconnect between the ideas about solidarity that are expressed and just how they might actually be enacted in society through the political process. Wilson writes:

Instead of rejecting air-conditioning—or all forms of comfort—outright, what I hope is that every time we push the ON button of a cooling unit, every time we enter a space that’s artificially chilled, every time we open the freezer—every time we engage in one of these everyday acts—we notice our terrible responsibility to each other.

Awareness of our global interdependence is certainly part of what’s needed, but Wilson pays scant attention to the power of NGOs in pressing capitalism to correct its course. I would argue that organizations such as the Union of Concerned Scientists, NRDC, and Ceres are rendering profound service in making the case for global climate action in the corporate sector. With myriad partners, they are concentrating citizen and corporate power, and driving a real wedge between entrenched fossil fuel companies and the rest of the corporate world. Yet Wilson writes that “mainstream environmental organizations cannot continue framing climate action as sacrifice. The shame, the moralizing, the exclusion, the call to give up comforts . . . these tactics don’t work.” This comes one page after he has told us that we need to feel “terrible responsibility” every time we reach for ice cream.

After Cooling doesn’t engage much with the real potential for political progress (AOC and the Green New Deal are never mentioned), and for a brighter, decarbonized future that could mitigate some of the need for austerity in general—and with respect to cooling specifically. This week I spent some time with the Department of Energy’s new Solar Futures Study, and I suggest that you check out the executive summary if you have a moment. I am also awaiting Saul Griffith’s new book Electrify; in the meantime, his interview with Ezra Klein is a good place to start. It is entirely possible that electric heat pumps and fuel cells will increasingly supplant traditional HVAC systems. Migrating the base of 1.6 billion residential AC units to higher-efficiency models also represents a significant opportunity. Grass roots campaigns for clean heat and clean air from groups like Mothers Out Front are gaining traction.

It’s true that far too many of our physical windows are closed. And it’s also true that the temporal window for action on climate is closing fast. It is certainly possible that we are too late to forestall disaster, on many fronts. But great minds and good people are hard at work, all over the world. Many folks like Sam are finding personal paths to action. Key institutions are beginning to move, belatedly but decisively. It seems possible to me that we are not so much living after cooling, but are instead gathering on the porch of the future, welcoming a storm of change.

Other Voices, Other Forms

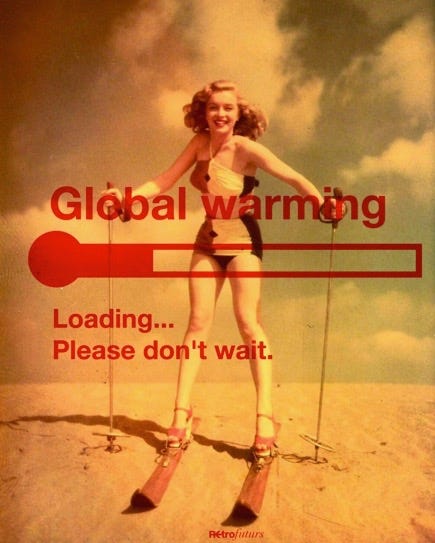

Stéphane Massa-Bidal is a French visual artist who works in collage, infographics, illustration, and typography. Here’s a poster design he created in response to an open source project by the artist-duo Sayler/Morris, who solicited posters from graphic artists addressing climate change.

Poem of the Week

Here is the beginning of Mikko Harvey’s poem “Grace Interrupted.” You can read the entire poem here.

For Your Reading Radar

Eminent British travel writer Colin Thubron has a new book entitled The Amur River: Between Russia and China. After a horseback riding accident, the eighty-year-old writer makes his way from northeast Mongolia to the Siberian coast, dodging the authorities and bonding with guys named Igor and Alexander, as he reflects on the age-old and evolving relationship between the two great nations.

For Your Calendar

Wisdomkeeper klaxon! Orion Magazine is hosting Robert Macfarlane, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and David Haskell for an online celebration of Old Growth, their new anthology of writing about trees. The event will be held Saturday, September 18th at 1 PM Eastern. The organizers write that “[t]hese authors bring a unique perspective on the legacy of trees in deep time, which they explore in their recent books Braiding Sweetgrass, Underland, and The Songs of Trees, respectively. Together they will discuss the idea of the personhood of trees, root communities, and the ways in which humans might foster the growth of our canopy.” More info is here.

Bookshop of the Week

This week I am linking to an indie bookstore in the the hottest city in the US: Phoenix, Arizona. Changing Hands is an important resource for the Phoenix/Tempe community, and has a really cool history.

See you next week . . . Nicie