Dear Reader,

More coastal flooding here this week. With just a two-foot storm surge on top of a not-especially-high full moon high tide, Conomo Point in the Great Marsh saw flooding from both sides. Though the panorama below is a bit distorted, it shows well how the access road to Robbins Island became completely impassable. Follow the telephone wires at left to discern where the road lies, beneath the encroaching waters of the bay. I asked a local woman if she had seen worse flooding, and she thought not. She paused and added, “It does seem like there is some kind of flood almost every month now.”

In the photo below, check out the mailbox as a reference.

As I continue to pay attention to changes where I live, climate change is also happening at the poles—but so much faster. There is even a term for it: “the new Arctic.” This week I want to share a book by one of the world’s most courageous and successful climate activists, someone who has been a true sentinel of the changing North.

Review

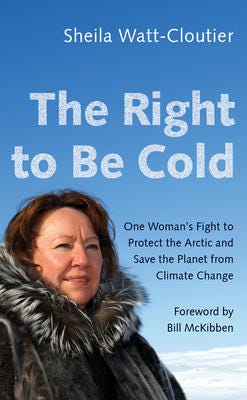

The Right to be Cold:

One Woman’s Fight to Protect the Arctic and Save the Planet from Climate Change

Sheila Watt-Cloutier

University of Minnesota Press, 2018

329 pages

$22.95

In the introduction to her memoir, The Right to Be Cold, Inuit leader and activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier explains that

[i]n our culture, hunting has taught us to value patience, endurance, courage, and good judgment. The hunter embodies calm, respectfulness, and caring for others. Silatuniq is the Inuktitut word for wisdom—and much of it is taught through the experiential observation of the hunt. The Arctic is not an easy place to stay alive if one has not mastered the life skills passed down from generation to generation.

The Arctic is not an easy place to stay alive. It seems worth dwelling for a moment on the collective achievement of the humans who have not only inhabited the circumpolar regions of the earth for over ten thousand years, but have thrived there. Watt-Cloutier, who was born in 1953, describes in detail the traditions—such as hunting with dog sleds and fishing in local rivers—that she grew up with in Kuujjuaq, a community in Arctic Quebec. She loved the Inuit diet, called country food, which is based on seal, salmon, caribou, whale, and ptarmigan, as well as berries and eggs gathered in summer. Her writing is at its most vivid when she describes the hunt that sustains both bodies and communities, and the meaning of country food in her life.

In his book Arctic Dreams, Barry Lopez notes in his description of a Yup’ik hunt that the discomfort of humans who no longer hunt for food often stems from their own disconnection from the land.

The entire event—leaving to hunt, hunting, coming home, the food shared in a family setting—creates a sense of wellbeing easy to share. Viewed in this way, the people seem fully capable beings, correct in what they do. When you travel with them, their voluminous and accurate knowledge, their spiritual and technical confidence, expose what is in insipid and groundless in your own culture.

Although she was raised by her mother and grandmother, who were leaders and healers (her non-native father had abandoned her mother), she also had strong male elders in her life and was close with her brother. Everyone had jobs to learn and perform—in hunting, gathering, and cooking, and in crafts including sewing, beading, and toolmaking. Boys were given jobs such as meticulously applying multiple layers of ice to sled runners, using moistened chunks of peat. The capacity for stillness and watchfulness that is so essential to success in hunting infused the culture: “. . . despite our home being full of people, there would be many quiet moments. People didn’t talk simply to talk . . . silences were accepted, companionable, and comfortable.”

Watt-Cloutier’s peaceful childhood was disrupted when she was sent south due to her gifted status to attend school at the age of ten, first living with a family in Nova Scotia and then at the Churchill boarding school for indigenous youth in Manitoba. The separation from her family and homeland was traumatic, but she did well enough in school to have dreams of becoming a doctor. Following in her mother’s footsteps, she returned home and worked as a translator and health aide in the local clinic. On a trip with her brother she met a firefighter, and later married him.

The demands of being a young mother of two forced her to abandon her path to medicine, but her work in the health clinic and then as a school counselor exposed to her to the rising public health crisis in Inuit settlements. Watt-Cloutier realized that the government policies of the preceding generation had inflicted inter-generational psychic damage. These policies had pushed the Inuit to hunt for the global fur market rather than for subsistence, to live in towns rather than seasonal camps, to send their children away to boarding schools, to eat southern processed foods. Taken together, this was a policy of coerced assimilation. Citing health concerns, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police carried out a horrific slaughter of thousands of Inuit sled dogs in the 1950s and 60s, which left deep emotional wounds and accelerated the loss of dogsled culture. Inuit communities, their men and boys in particular, began to suffer extraordinarily high rates of depression, substance abuse, and suicide. Crime became part of everyday life, and a culture of dependency took root.

Eager to reform a system in which children were struggling on many levels, Watt-Cloutier made her first foray into politics, joining the local school board. She fought for a curriculum that would instill Inuit values and life skills, and foster local accountability. She found her voice, and learned how to deal with entrenched opposition. A leadership role with the Inuit governing corporation in Quebec led to her nomination and election in 1995 to the presidency of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC). The ICC is a multinational NGO representing the interests of the approximately 160,000 indigenous people who live in Greenland, Canada, the United States, and Russia. Watt-Cloutier was now operating on a global stage.

Immediately she found herself with a major fight on her hands: to convince countries around the world to severely restrict use of a group of chemicals, including PCBs and the pesticide DDT, that produce persistent organic pollutants (POPs). POPs migrate around the globe from industrialized and developed areas, through air and water cycling. In the Arctic they accumulate at high rates in the fatty tissues of the very animals that form the core of the Inuit diet, and even pollute the breast milk of young mothers (see Issue 24). The negotiations took years. Watt-Cloutier details her work to build coalitions, to deal with opposition from countries that use DDT for malaria prevention, to engage with the media, and to walk the tightrope of raising the alarm globally while reassuring her constituents. The resulting 2004 Stockholm Convention, like the Montreal Protocol for HFCs (see Issue 23), was a massive multilateral achievement with one notable difference: the United States did not ratify it, thanks to opposition from Republicans in the US Senate, who would not support legislation to make it enforceable.

The ICC’s campaign to restrict POPs prepared Watt-Cloutier for her next serious challenge: raising the alarm globally about the accelerating and potentially devastating effects of climate change in the Arctic. In 2003, the US State Department under George H. W. Bush threw sand in the gears of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment process, given domestic political concerns in an election year. Watt-Cloutier became a canny and at times controversial player, winning over Senator John McCain with stories of how the US military had helped the Inuit during World War II, and encouraging him to apply pressure to move ahead with the study. The thousand-page 2005 report that ensued represented a landmark of cooperation between Western-trained scientists and Inuit knowledge-keepers. It includes reports from many hunters on changes they had observed in weather patterns and local ecosystems.

Contrary to our beliefs and ability to predict [by] looking at the sky, especially the cloud formations, looking at the stars, everything seems to be contrary to our training from the hunting days with our fathers.The winds could pick up pretty fast now. Very unpredictable. [The winds] could change directions, from south [to] southeast in no time. Whereas before, before 1960s when I was growing up to be a hunter, we were able to predict. ~L. Nutaraluk, Iqaluit, 2000

Watt-Cloutier’s last major activist push was to use the ACIA report as the basis (along with the testimonies of 62 Inuit) for a petition to the UN’s Commission on Human Rights. It was a petition for the right to be cold. She argued that historical CO2 emissions by the US amount to a human rights violation against Inuit people, degrading their environment and making their way of life increasingly dangerous and untenable. Likely due to US pressure behind the scenes, the UN declined to hear the petition. Yet Watt-Cloutier’s innovative tactics in seeking redress for climate harms to humans, and positing a habitable environment as a human right, will no doubt serve as inspiration for future efforts.

I was glad that the book interleaves the political history, dense at times with acronyms and conferences, with her personal journey through life’s inevitable joys and losses, and her efforts to learn more about her father. When the personal and the political come together around the time of her Nobel Peace Prize nomination in 2007, she offers moving reflections on global realpolitik and the definition of personal success. We can only hope that many more native people will write their stories. University of Minnesota Press, Watt-Cloutier’s US publisher, has a strong commitment to Indigenous topics.

In the bitterest of ironies, the melting of Arctic sea ice is creating a new rush of interest from extractive corporations eager to begin drilling and mining operations in heretofore inaccessible places. Sheila Watt-Cloutier closes with a plea to her fellow Inuit to resist the lure of potential riches, which may well be accompanied by the loss of moral high ground in addition to further environmental damage. She takes rightful pride in the role that Inuit people have played—in no small part thanks to her leadership—as “responsible sentinels of environmental change.” With their intimate knowledge of a place where it is not easy to be alive, they have done their very best to warn us that life for all of us is going to become much, much harder.

Other Voices, Other Forms

The Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG), which holds the world’s largest collection of contemporary Inuit art, recently opened an addition with the name Qaumajuq. In the Inuktitut language this word means “it is bright, it is lit.”

The inaugural exhibition is a contemporary survey, and you can take a walk through with it this video narrated by a range of Inuit voices, including some of the artists. There is also an exhibition of Inuk style and fashion. Read here about the design process for the new building, which was led by architect Michael Maltzan.

Poem of the Week

Poet Joan Naviyuk Kane is a member of the Inupiaq people, and she writes in both Inuktitut and English. Her poem “Exceeding Beringia” was commissioned by the Academy of American Poets. It celebrates sites in the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, which encompasses 2.8 million acres in the Arctic, and also honors the memory of Herbert Agiygaq Anungazuk, an Inupiaq cultural anthropologist who served as a liason between the National Park Service and Native communities. Here is the opening.

"I remember the birds ever so many of them when I hunted with the weapons of a child. The water was covered in their numbers, red as the flowers of summer on the mountain. The red phalarope were our prey of choice, there were so many. Today, these birds return yearly, but now only a few return home in spring to show us they remain a part of the land, as we are." —Herbert Agiygaq Anungazuk

Nimiqtuumaruq aktunaamik: bound

with rope.

This land with its laws that serve as wire

and root to draw us together. Sinew,

snare,

the unseen growth of the green tree

many rivers south whose stump now

shoals

into use. Through layer upon layer of

land

submerged, of ice, of ash, through lakes

that cannot be the eyes of the earth.For Your Reading Radar

“It gets very dark when we don’t have any snow,” a Sami official in northernmost Norway tells Ben Rawlence, author of the new book The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth, which is out in the UK and will be released in the US on February 15th. Rawlence follows the boreal forests of the world as they march north due to global warming, at a pace that has reached 40 km per year in some locations (!). The publisher describes the book as “a journey of wonder and awe at the incredible creativity and resilience of these species and the mysterious workings of the forest upon which we rely for the air we breathe.” A compelling excerpt from the book is available now via The Guardian.

For Your Calendar

A new documentary titled “Ice Edge: The Ikaagvik Sikukun Story” has just been released for viewing on YouTube. The film follows a multi-year research collaboration between Inupiaq hunters and scientists, with the goal of understanding changes in the sea ice in Alaska.

Columbia University’s Climate School is hosting a launch event via its Sustain What webcast series on Thursday, January 27 at 10-11:30am Alaska time and 2-3:30 pm EST. Details are here.

Bookshop of the Week

Massy Books in Vancouver, BC is an indigenous-owned bookshop, performance space, and art gallery located in the Chinatown neighborhood.

Happy reading and see you next week. xo Nicie

Cover Image: Pudlo Pudlat (1916-1992), Women at the Fish Lakes, 1977. Lithograph on paper. Government of Nunavut Fine Art Collection. On long-term loan to the Winnipeg Art Gallery.