Issue 6 — Dancing with Fireflies, Swimming with Sharks

World of Wonders, by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Dear Reader,

We have had a quiet week, but an exciting one in its own way. My daughter Grace Panetta celebrated publication day for the new book A Return to Normalcy? The 2020 Election That (Almost) Broke America, edited by the team at UVA’s Center for Politics. Grace contributed a chapter on election administration and voting in the pandemic, and on April 8th she led a spirited (if somewhat dispiriting) panel discussion with three of her co-authors on the societal impact of the 2020 elections. Also, I scored an appointment for my first jab, which I’ll be getting this weekend.

Thanks to all of you who have been in touch. I’ve had some nice requests for a gift subscription option, so voilà! May I humbly suggest that a Frugal Chariot subscription might be a nice Earth Day gift idea, as is this week’s book, World of Wonders.

Review

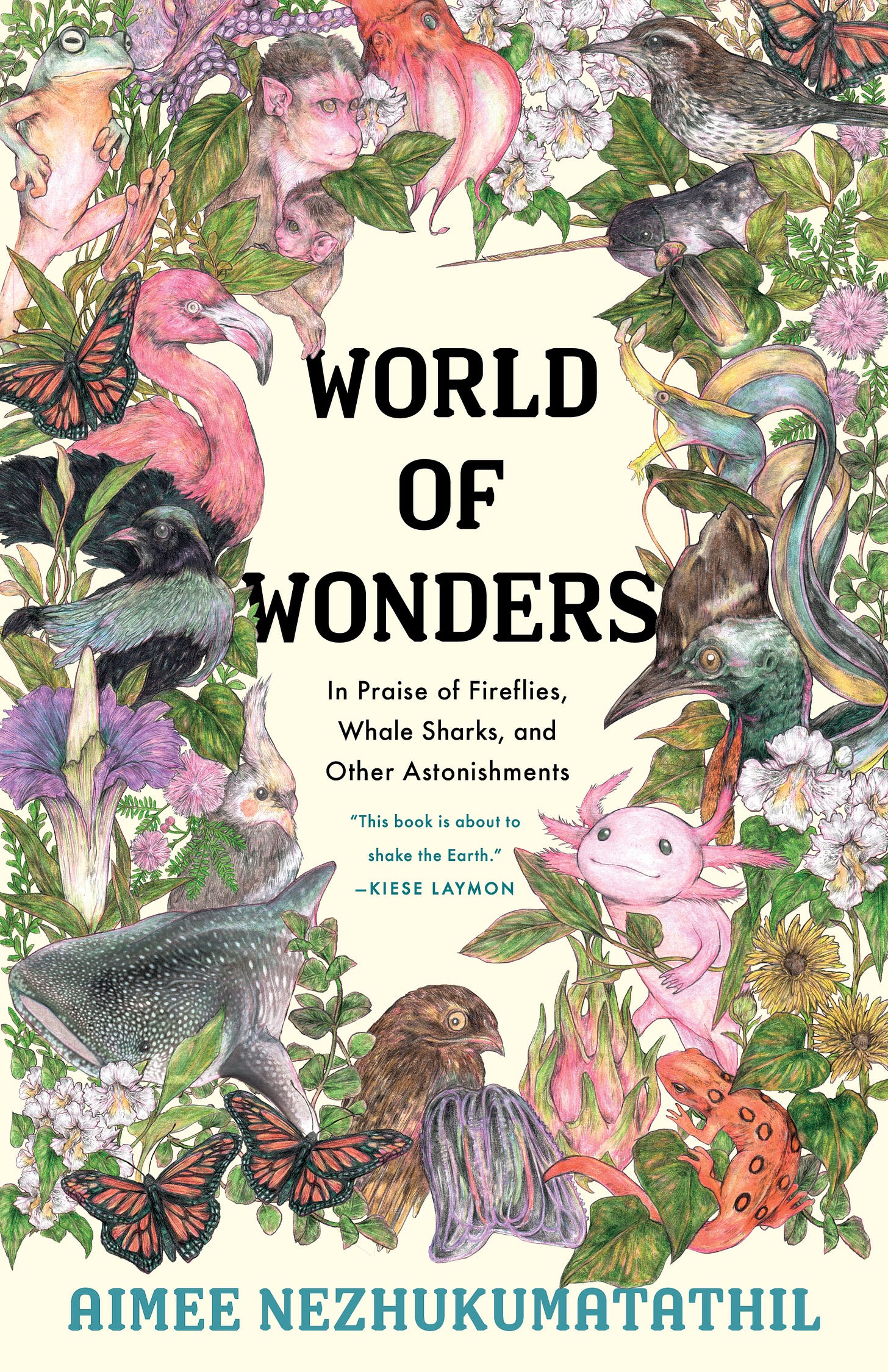

World of Wonders:

In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments

Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Milkweed Editions, 2020

165 pages

$25.00

If a white girl tries to tell you what your brown skin can and cannot wear for makeup, just remember the smile of an axolotl. The best thing to do in that moment is to just smile and smile, even if your smile is thin. The tighter your smile, the tougher you become.

So begins Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s appreciation of a salamander with regenerative abilities that have scientists enthralled. In just a few pages, she twines her approach to dealing with micro-aggressions around the extraordinary attributes of this foot-long amphibious carnivore, an animal that can not only regrow a severed limb, but even an amputated jaw. Without scar tissue. These are interesting superpowers for a kid of color trying to thrive in a racist society.

Nezhukumatathil’s latest book World of Wonders is a memoir spun out of praise songs for an array of species that she holds dear. Indeed, her prose spins, pulses, and crackles with the energy many of us know and love in her poems. From the catalpa tree and the cactus wren, to the dragon fruit and the vampire squid, these marvels of creation meet up with memories that span from childhood to motherhood, in essays that have the rhythm of dance and the richness of a feast.

Aimee Nezhukumatathil is a professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Mississippi. She has written four books of poetry and also an epistolary chapbook about gardening, which presents an exchange with the poet Ross Gay. Born in Chicago to a mother from the Philippines and a father from Kerala in India, she grew up in places as diverse as Chicago, Kansas, Arizona, Upstate New York, and Ohio. Wherever she lived, and whatever the heartache, she found allies and inspiration in the living world around her.

In an early essay in the book, her portrait of a peacock made for a drawing assignment in school draws a rebuke from a teacher: “Some of us will have to start over and draw American animals. We live in Ah-mer-i-kah!” What follows is a scene that speaks to the emotional and spiritual toll of cultural assimilation when it is forced upon children and their families. Later, as a latchkey kid in 1980s Phoenix, when child abduction was a widespread fear, she made common cause with the cactus wren, who knows how to use the sentinel cactus as a protective home.

Perhaps I wanted to be like the inhabitants of the cacti—those wily birds with a nutty cap of feathers like a brush cut gone awry on their heads, who didn’t seem afraid of anything in the harsh and unforgiving desert, no matter their size.

Aimee Nezhumatathil conjures her subjects and their ecosystems with short strokes and flourishes, taking us from the edges of the suburbs to the depths of the ocean.

Way down deep, in the perpetual electric night of the water column—a place where sunlight doesn’t register time or silver filament—the vampire squid glides in search of a meal of marine snow. These lifeless nits of sea dander are actually the decomposing particles of animals who died hundreds of feet above the midnight zone. The vampire squid reaches for this snow with two long ribbons of skin, which are separate from its eight tentacles. If it is truly hungry, it trains its eye on a flow, the lure of something larger—a gulper eel, perhaps, or an anglerfish waddling through the inky water. The squid’s eye is about the size of a shooter marble, but this is nevertheless the largest eye-to-body ratio of any animal on the planet.

Once she has caused us to fall in love with this mysterious creature, and its superpower of flight and disappearance, she shows us how she herself was like the vampire squid during a painful year of transition to a new high school: dealing with the dreaded dilemma of the lunchroom by eating her sandwich in a bathroom stall. She emerges over time aided by her inner strength, by the making of friends, by the encouragement of teachers, and by the discovery of writing.

I emerged from my cephalopod year, exited my midnight zone. But I am grateful for my time there. If not that shadow year, how would I know how to search the faces of my own students? Or to drop everything and check in, really check, with each of my sons . . .

There is so much breadth of life in this book, as we move through childhood into the author’s adult life as a writer, teacher, wife, and mother. We travel with her to visit family in Kerala, to visit Greece for a moving encounter with an octopus, and to visit her parents in retirement, with their lovingly tended fruit trees and their cockatiel, Chico.

Cockatiels are famous for their “cheddar cheeks,” tiny wheels of orange on each cheek, making them the little clowns of the bird world. They are about three apples tall and slightly lighter than a deck of cards . . .

“The most sensuous poets are ones that I trust the most, because I can undergo their poems, I can arrive at their emotions, by having undergone their sensations.” These words from poet Jorie Graham speak to Nezhukumatathil’s art. It’s not just that her language is sensuous. It’s that the formal juxtapositions between non-human and human struggles generate their own sensations of drama and elicit emotion in the reader. When a school-bus-sized whale shark swims so close to Nezhukumatathil that she could touch it, we hold our breath with her, and think of her children, too.

I must add that the beauty of this book extends very much to its design and illustrations. Fumi Mini Nakamura’s watercolors in World of Wonders are as lush and delicate as the prose. The book is set in Essones, a gorgeous typeface that is only a few years old. It was designed by James Hultquist-Todd, who has a background in bespoke tailoring and auto upholstery (!).

Jorie Graham made her statement about sensation and trust in a recent interview on David Naimon’s brilliant long-form literary podcast, Between the Covers. Graham, whose new volume Runaway completes a tetralogy of books on the theme of climate disaster, also invoked Robert Frost:

There are no two things as important to us in life and art as being threatened and being saved . . . All our ingenuity is lavished on getting into danger legitimately so that we may be genuinely rescued.

For me, this is exactly what makes World of Wonders a necessary book. With her portraits of entangled human and non-human lives, she helps us to feel their dangers as we do our own, and so legitimates those dangers not as a matter of information, but as a matter of peril from which we all need deliverance.

Jorie Graham continues, referring to the sensorium, or seat of sensation, and makes the argument that humans need to actively re-awaken all their senses at a time when the visual (looking at you, Instagram!) has overtaken the others (smell, taste, hearing, touch):

My feeling is that if we awakened the communal that we share, we’re not going to hear, smell, touch that differently [from each other]. If we can just awaken the sensorium, we can begin to talk about emotions that rise up out of the sensorium. As Keats would say, emotions and philosophy and ideas are not real until they are “tested on the pulse,” by “the pulse” he means the senses. And if we could make our emotions communal, wouldn’t that be astonishing? If could share an understanding, as opposed to having reacted to intellectual, dry emotions, which we tend to have in our day and age, based on opinion. What if our emotions rose up out of much more trustworthy layers in us which are the shared places with other humans of all different kinds of experiences and all over the planet using different languages, living different lives?

We are not going to be able save our ecosystems with data or analysis. We’ve had those things for decades. The scientists are convening the poets and the artists because they know, to their distress, that presenting the public with the information and insight they have dedicated their lives to producing has not resulted in the necessary changes.

I googled the axltotl. When I typed in “is the axlotl . . .” Google finished my question. “Is the axlotl in Minecraft yet?” Five of the top ten hits for the simple Google search of “axlotl” are Minecraft-related. My actual question was: Is the axlotl still living in the wild? The answer is maybe—just barely. In recent years, its habitat had been reduced to two fresh-water lakes in Mexico. One was drained by authorities. The other is now teeming with invasive carp who eat the axlotl’s eggs. Less than one thousand axlotls are believed to remain living in the wild, so you will need to go to a lab, a zoo, or a pet store to see one. Or you can log in to Minecraft.

World of Wonders begins and ends with reflections on the firefly. Nezhukumatathil shares that in a recent visit to an elementary school, “seventeen students in a class of twenty-two told me they had never seen a firefly—they thought I was kidding, simply inventing an insect.” She had to pull up a video on YouTube. I guess they don’t have fireflies in Minecraft just yet. I find it overwhelming to think of how disconnected most of us are from nature, but I try to take some heart from all the young families I have seen in the woods during this last year.

Where does one start to take care of these living things amid the dire and daily news of climate change, and reports of another animal or plant vanishing from the planet? . . . Maybe what we can do when we feel overwhelmed is to start small. Start with what we have loved as kids and see where that leads us.

In a sense, that’s what I am trying to do with this newsletter. Starting small. Starting with what I have loved and do love now. Hoping to build trust with you in a time of real dangers, Dear Reader, and to make common cause in the rescue mission that requires our fullest possible commitment.

Other Forms/Other Voices

How about this recent painting of deep sea creatures by Fumi Mini Nakamura!

And if you haven’t seen it, My Octopus Teacher is a superb documentary on Netflix, about a South African nature photographer who swims his way out of a midlife crisis with the help of an octopus.

Poem of the Week

World of Wonders is very much an invitation, and here is Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s poem, Invitation.

For Your Reading Radar

More books for birders! A Most Remarkable Creature: The Hidden Life and Epic Journey of the World’s Smartest Bird of Prey by Jonthan Meiburg is now out. The author travels the world to track and understand the rare striated caracara, which is—to paraphrase E. B. White—some bird. No, I’d never heard of it either. You can watch Meiburg in conversation with Stephen Sparks of Point Reyes Books on Thursday, April 15 at 7 PM Pacific time.

For your Calendar

Also on April 15th, at Noon Eastern time, the Museum of the City of New York will be hosting a panel discussion connected with their new exhibition Rising Tide: Visualizing the Human Costs of Climate Crisis. Panelists include a Dutch diplomat who focuses on water affairs, a Bangladeshi environmental activist, a glaciologist at Columbia University, and also the Dutch photographer Kadir von Lohuizen, one of the artists who is represented in the show. Von Lohuizen’s new book After Us The Deluge: The Human Consequences of Rising Sea Levels will come out on April 30th.

Bookstore of the Week

This week we are linking to Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi. Oxford is home to the University of Mississippi, where Aimee Nezhukumatathil teaches. This fine shop, which has a fascinating history, currently has in stock signed copies of World of Wonders.

That’s it for now. Enjoy the weekend. We’ll be in the garden. xoxo Nicie

I'm delighted to be included in your rescue mission — thank you, Nicie.