Dear Reader,

Last week I quoted Irene Solà, who has said that the subject of her novel When I Sing, Mountains Dance is “the cruel optimism of life.” Today I am struggling to get past the cruelty of a society that does nothing when its Black grocery shoppers and tiny school children are targeted and massacred. It is hard to locate optimism on any map.

But we can find good work. And we can find beauty. On the good work front, I take heart from the organizations and individuals who are putting body, mind, and soul into the movement for gun control in this country. They deserve our support and our participation.

On the eco-literary front, more good work: two of our finest environmental writers, Bathsheba Demuth and Kerri Arsenault, have launched TESS — The Environmental Storytelling Studio at Brown University. The studio is designed to provide coaching for academics who want to write about environmental subjects for the broadest possible audience. What a great initiative.

And beauty. Our bank of Siberian iris, lovingly divided and tended by my husband over the years, is now blooming. When the wind surges through the garden, the sweep of bloom looks like a wave breaking .

And a housekeeping note. I am adopting the publishing industry’s summer hours approach, and therefore the Chariot is going to roll a bit differently during the next three months. I will be sharing a review every two weeks, and offering brief reflections from my summer journeys in the intervening weeks, in a new section of the newsletter called “Bird on the Wing. I’ll make the first couple of “Bird on the Wing” installments public, and after that they will be for paying subscribers. Destinations will include the Lost Coast of Northern California’s Humboldt County, London, Portugal, and Maine. My planned interview series with environmental leaders will commence in the Fall.

Review

A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds

Scott Weidensaul

W. W. Norton, 2021

385 pages

$18.95

On an October morning in the early 1970s, twelve-year-old Scott Weidensaul climbed a mountain in Western Pennsylvania, tucked in among some boulders, and witnessed a “big flight” of hawks migrating south for the winter.

Hundreds of raptors glided down the ridge that day, surfing the invisible waves of air, and I started hungrily through my cheap binoculars, as each passing hawk dragged my eyes along with it. . . . The spectacle was easily the most intoxicating thing I had ever witnessed . . . I slept very little that night, and my dreams were full of wings. Half a century on, I am still captivated by migration.

Fifty years later, and still inspired by bird migration, Weidensaul is one of the leading journalists writing in English about birds. His book Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere With Migratory Birds (2000) was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. He has also written guides to owls and raptors, a chronicle of birding in the United States, as well as books on the natural and human histories of North America. A World on the Wing (2021) is in some respects a world-spanning sequel to Living on the Wind. Weidensaul brings us a globe-trotting, up-to-date account of efforts by a community of experts and enthusiasts to understand more about avian migration, and also to help slow the declines—in some cases precipitous—in the populations of migratory birds.

Weidensaul writes from the sweet spot of amateur expert. He is a practicing bird researcher, who has been part of leading-edge projects to band and tag birds with ever more sophisticated monitoring devices. And he brings his writer’s gift to setting the scenes for these initiatives, which often require researchers to place themselves in uncomfortable and risky situations. The author takes us to the arctic tundra where grizzlies roam, to the mud flats near Shanghai where rampant development has created a narrow bottleneck for millions of migrating shorebirds, to the eerie military zones of Cyprus where millions of migrating songbirds are trapped and slaughtered for food by poachers, and to Nagaland, the remote part of India where a nascent eco-tourism movement may hold the key to stopping the trapping and mass killing of Amur falcons.

It is especially interesting to read the Cyprus chapter in contrast to another book chapter set in Cyprus’s strip of no-man’s land, which is included in Cal Flyn’s Islands of Abandonment (see Frugal Chariot Issue 29). There the absence of humans has allowed many species to thrive. I wonder if the birds will eventually learn to congregate in the no-man’s land, and avoid the acacia groves specially grown by trappers in order to lure them.

The stakes of these projects are existential for migratory birds, who are trying to survive three major threats: habitat loss and human building, precipitous insect population declines at the base of their food chains, and what Weidensaul calls “the big enchilada” of climate change. As many as one billion birds per year die from flying into buildings in the United States. A 2019 study of North American populations estimated that since 1970, when Scott Weidensaul first fell in love with birds, “some 3.2 billion birds—almost 30 percent of the continent’s total breeding populations—have disappeared from North America.” These losses have been most severe in the East, where habitat destruction has been profound both in the tropics and on the Eastern Seaboard. This study put the lie to the idea that “specialist” birds that require specific habitats are the losers, while generalists do fine: starling and sparrow populations have fallen 50 to 80% in the same time frame. Globally the news is every bit as grim, with a 2018 study documenting a 30% decline in France over just 15 years. Climate change is creating a storm of changes in seasonal weather patterns, storm intensity, food source availability, and habitat loss. All these factors make migration riskier. You can’t help rooting for the birds as Weidensaul recounts their efforts to adapt their journeys. I think of Emily Dickinson’s poem:

Hope is the thing with feathers That perches in the soul, And sings the tune without the words, And never stops at all, And sweetest in the gale is heard; And sore must be the storm That could abash the little bird That kept so many warm. I've heard it in the chillest land, And on the strangest sea; Yet, never, in extremity, It asked a crumb of me.

One could not ask for a better survey than the one A World on the Wing provides. It offers deep detail on the scientific race to understand just what is happening to migrating birds, and cogent explanations of the various attempts to assist them in their journeys. Weidensaul describes advances in transmitter technology and satellite networks, as well as laboratory science that is providing insight into avian wayfinding. There is lots of dogged heroism on display in these pages, and some notable successes. Yet ethical considerations abound. Scientists aren’t merely trapping and banding. They must decide how much tracker weight can be placed on the backs of the tiniest birds and fledglings. For certain studies, they are taking young away from their nests and later returning them. They are trapping rare birds to breed them in captivity. No doubt these interventions are all undertaken within the context of careful ethical reviews. But they are also all invasions of these creatures’ bodily autonomy.

More troubling are the massive slaughter programs, also chronicled in Adam Nicholson’s memoir Sea Room, targeting mammals like rats, mice, and cats that prey on birds, especially on islands that serve as seabird nesting colonies. Human marine traffic has been responsible in the first place for “spilling” these mammals onto remote islands. Now humans, who continue to slaughter birds in untold billions for food, are also slaughtering the other animals that eat the birds we don’t want to eat. In certain venues, airplanes drop huge quantities of poisoned pellets and lethal peanut butter chew cards across the terrain. It is interesting to note that in a book loaded with population numbers, Weidensaul provides no estimate of the numbers of mammals killed in these programs. How the decay of so many toxic corpses might affect local ecosystems is a question also unaddressed.

One can appreciate the well-intentioned rationales for such conservation efforts, and yet still be unsettled by the heavy hand of human dominion over virtually every ecosystem, no matter how remote. Weidensaul himself writes that when it comes to birds, “their future, for good or ill, lies in our hands.” I am reminded of Merlin Sheldrake’s book Entangled Life (see Frugal Chariot Issue 25), in which humans are described by one source as (I paraphrase) “exceptionally clever and destructive monkeys.” We burn, we build, we cook, and we consume on a scale that other creatures struggle to survive—unless we are breeding them for our use. A World on the Wing is an excellent book. Yet I came away from it mournful that the monkeys, by turns rapacious and benevolent, are the overlords of the birds.

Other Voices, Other Forms

The National Audubon Society has just launched a new audio collaboration project called For the Birds: The Birdsong Project. Renowned Hollywood music supervisor Randall Poster, who took up birdwatching during the pandemic (“I was [previously] more of a squirrel person”) has overseen the contributions of over 220 creatives, and has crafted them into five volumes. Volume One dropped this week on Spotify, and it includes new music from Beck, Nick Cave, and Hatis Noit, as well as poetry readings by Tilda Swinton and Jelani Cobb.

Poem of the Week

We turn again to W. S. Merwin, and his poem “Shore Birds”—courtesy of The Merwin Conservancy.

SHORE BIRDS While I think of them they are growing rare after the distances they have followed all the way to the end for the first time tracing a memory they did not have until they set out to remember it at an hour when all at once it was late and newly silent and the white had turned white around them then they rose in their choir on a single note each of them alone between the pull of the moon and the hummed undertone of the earth below them the glass curtains kept falling around them as they flew in search of their place before they were anywhere and storms winnowed them they flew among the places with towers and passed the tower lights where some vanished with their long legs for wading in shadow others were caught and stayed in the countries of the nets and in the lands of lime twigs some fastened and after the countries of guns at first light fewer of them than I remember would be here to recognize the light of late summer when they found it playing with darkness along the wet sand

For Your Reading Radar

Ever prolific, Scott Weidensaul has just published his first children’s book, A Warbler’s Journey, illustrated with lush paintings by artist Nancy Lane for readers aged 5-8. Weidensaul tells the story of a single bird’s migration and the families that encounter it along the way. J. Drew Lanham, a professor at Clemson and author of the beautiful memoir The Home Place, says “A Warbler's Journey is masterfully woven words of wonder written with hope as a warm tailwind. It is art and science about a tiny bird that will make a big difference.”

For Your Calendar

Point Reyes Books has assembled an ensemble of eminences to celebrate the posthumous publication of previously uncollected essays by Barry Lopez, in the volume Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World. The lineup includes Robert Macfarlane, Jane Hirshfield, and Bathsheba Demuth. The webinar will be held on Thursday, June 2 at Noon Pacific time. Register here.

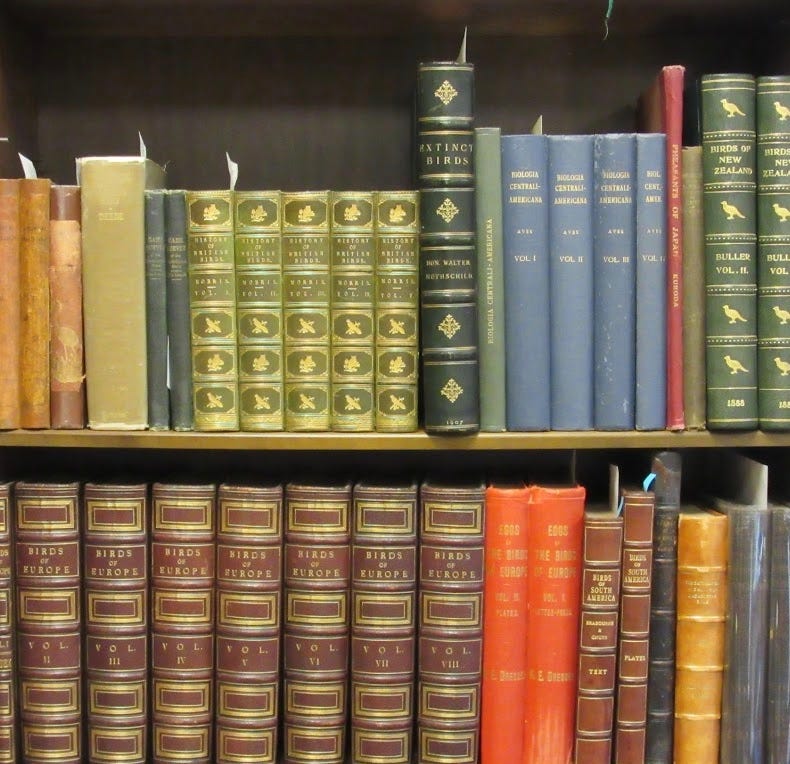

Bookshop of the Week

Buteo Books is America’s leading seller of bird-related books, stocking “the largest selection of ornithology books in North America; over 2,000 titles in print, including field guides, finding guides, and scientific textbooks. We offer hundreds of rare and out-of-print books, from bargain used books to rare antiquarian volumes.” They don’t have a store per se, but you can visit their warehouse in Arrington, VA.

That’s it for this week. Take care of yourself. xo Nicie

The artwork in this week’s issue is by Catherine Hamilton, a California-based artist.

The cover image is “Orchid and Two Hummingbirds” by Martin Johnson Heade (1871).