Dear Reader,

It’s a tree peony riot here, and the bees are loving it.

Some news: I have a review out in a different publication, namely the excellent digital literary magazine Necessary Fiction. I wrote about the small-town coming-of-age novel When Me and God Were Little, by the Danish writer Mads Nygaard (translated by Steve Schein). I hope to write more in the future for Necessary Fiction, which publishes original short stories in addition to reviewing fiction (especially in translation) from small independent publishers.

I’ll also mention that fans of the Ocean State may be interested a debut novel that came out this week: Ready, Set, Oh! by one of NF’s editors Diane Josefowicz. According to the publisher, Flexible Press, the book is set in Providence, Rhode Island, “against the upheavals of the Sixties and chronicles the struggles of a man who has just lost his draft deferment, a young pregnant woman with fragile mental health, and a UFO-chasing astronomer, each hostages in their own way to their families and to history.” As a historian, Diane is the author (with Jed Z. Buchwald) of two landmark studies in Egyptology: The Riddle of the Rosetta (2020, and out in paperback this week!) and The Zodiac of Paris (2010), both from Princeton University Press.

One more thing before I turn to this week’s review. I discovered this book via the Point Reyes Books subscription series called Thinking Like a Mountain. Over the course of a year, PRB will send you a series of special books about the living world, with supplementary material and author interviews. I have loved every book they have sent me this past year.

Review

When I Sing, Mountains Dance

Irene Solà, translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem

Graywolf Press

203 pages

$16.00

Come here, come, I shall give you a stretch of my back so you can build a house there.

So speaks the mountain.

There is no pain if the pain is shared. There is no pain if the pain is memory and knowledge and life. There is no pain if you are a mushroom! Rain fell and we grew plump. The rain stopped and we grew thirsty. Hidden, out of sight, waiting for the cool night.

So speak the mushrooms.

I’ve got poetry in my blood, in my veins. I keep all my poems in my head as if inside a tidy drawer. I’m a vase filled with water. Simple fresh water like the springs and runnels. I lie down and the verses just pour out.

So speaks the poet, who is a ghost. Who is the son of a poet, who is also a ghost.

These are but three of the many voices in the chorus of Irene Solà’s smashing novel When I Sing, Mountains Dance, in which the distinctions between the human and the non-human, the living and the non-living, fall away before the singularity of each character’s essence and timbre. Every chapter is joyous, and a joy to read. When I Sing tells the story of a particular landscape in the mountains of Catalonia, near the border with France, and of a family for whom death can come as fast as a lightning bolt or a gunshot, but whose spirits linger long and partake of the future.

Irene Solà is a visual artist and poet as well as a writer of fiction. Her first novel El Dics (The Dams), published in 2018, won the Documenta Prize. When I Sing, Mountains Dance has been a strong seller in Spain. It was awarded the European Union Prize for Literature, and is being translated into twenty languages. The novel has been staged as a play, and its black chanterelles have even inspired a work of music. Shearsman Books in the UK has published Solà’s poetry collection Bèstia (translated by the author and Oscar Holloway).

In the world of experimental novels, When I Sing is a raucous jamboree with soul. The word “experimental” might conjure the prospect of the disjointed, the overly serious, the theoretically-determined—or all three at once. Reader, worry not. Solà pulls off the virtuosic feat of presenting eighteen chapters narrated by eighteen different characters, all without ever allowing the narrative energy to flag. She accomplishes this by unfolding across the entire book the story of a single family: the farmer Domènec, his wife, Sió, their daughter Mia, and their son, Hilari. Domènec is killed by a lightning strike in the opening chapter, which is narrated by the thunder clouds. He had been out gathering mushrooms, and the ghosts of four women who were executed as witches during the Inquisition quickly appear to survey the scene and abscond with his black chanterelles, triumphing over their persecutors for eternity, with wild laughter.

Solà has said that the family’s story is like a river that flows through the entirety of the book. In some chapters you will be right on its shores, while in others you might hear only the sound of it in the distance. As a reader, I felt the plot working on me in just this way, and the culmination of its great love story brought an unexpected rush of emotion. Mara Faye Lethem notes that El Dics is a novel about narrative, and Solà has said that seeds she planted in that book went on to germinate in this one. It’s also the case that When I Sing is a book about poetry, and about what poetry can be to any of us—and to all of us. Domènec and Hilari are both poets, and nearly every sentence in the novel has the movement of poetry. Here is the character Oriol, describing Mia:

Mia has the equilibrium of embers, and it makes you calm, it makes you feel like laughing again, and drinking coffee, and makes you want the summer to arrive, and the autumn, or whatever it is that must arrive. Her face is like a tree with two eyes like two ladybugs, and her mouth, hushed, and she just exudes peace, until suddenly she says something caustic as if there’d been a fire below the surface the whole time but I was only just listening.

While I would never call for compulsory versification, as I read prose like this by a poet, I can’t help thinking that for the rest of my life I want all my prose from the poets. Can you imagine a world in which the forms at medical offices were created by poets? We’d look forward to getting our teeth worked on. I bring this up because When I Sing, Mountains Dance is the sort of book that makes you want to get up and hop around the room when you are reading it. Solà’s text practically vibrates with its rousing rhythms. Its suites of sentence fragments make one think of energetic gavottes, or deft disco moves. But then again, perhaps one could argue the opposite of my point, because Mara Faye Lethem has produced an astonishingly powerful translation (her rendering of Mia’s dog’s voice in English is a tour de force on its own)—and as far as I know, she is not a published poet. Whatever the case, I will be seeking out more work from both of these writers.

The way time and history work in this book relates to these metaphors of “the equilibrium of embers” and “a fire below the surface.” When the mountain speaks in this book, it reminds us that it lives in geological time. Its rhythms are the rhythms of the Earth’s plates, and of the molten rock that swirls and surges beneath them. Every element, every creature in the landscape has its own life span. And the death of one is often unremarked by or unremarkable to the others; the bees keep buzzing and the cattle keep grazing. In a recent appearance, Solà called this situation the “cruel optimism of life,” and the way her book overlaps lives and deaths on one piece of ground summons a special context for pondering history. In Solà’s mountain world there is no escape from history: from the Inquisition, from the Spanish Civil War, from the separatist movement in Catalonia, which includes the fight for the Catalan language itself. But history, with its own equilibria and eruptions, also operates within limits—in terms of what it can do to repress, to dispossess, to destroy.

One of the characters in When I Sing, Mountains Dance (based on a real child documented in the famous photograph above) is Palomita, the ghost of a child amputee who fled on crutches after a bombing with her family across the mountains during the Spanish Civil War and died in France. Her spirit has returned to the Pyrenees.

I went back to the forest alone because it was a tranquil and happy forest, on a happy mountain, for a happy little dove like me . . . When we fled through this place you could barely see the river. Maybe it was scared, too, and hiding, and you could hear it only like a frightened whisper. But if you found it just once, and you saw it once, that was it. It was yours.

That sense, not of ownership but of belonging, of all things belonging to each other across and beyond time, is the triumph of this jubilant book.

Other Voices, Other Forms

Summer 1993 is a lyrical story of childhood in rural Catalonia, created in 2018 by filmmaker Carla Simón. Based on Simón’s own experiences, the film tells the story of a young girl who is taken in by her aunt and uncle after her mother dies. It is available to stream free for Prime Video subscribers and for a fee on YouTube.

Poem of the Week

Granta has published a series of five poems by Irene Solà, translated by Oscar Holloway. Here is one.

I wore off my tongue like candy, and by the end of summer I lost leaves and petals. The cave in my palate was empty for three thousand years. Neither paintings, nor campfires. I would say with my eyebrows: how beautiful, the heights! how beautiful, the glaciers!

For Your Reading Radar

Fans of the great American painter Winslow Homer will want to seek out the impressive new biography by my friend and neighbor William Cross, entitled Winslow Homer: American Passage. Writing in The New Yorker, Claudia Roth Pierpont calls the book “scrupulous” and “a pleasure to read.” Those in the New York area may wish to read it in conjunction with a current exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents” will be on view through July 31.

For Your Calendar

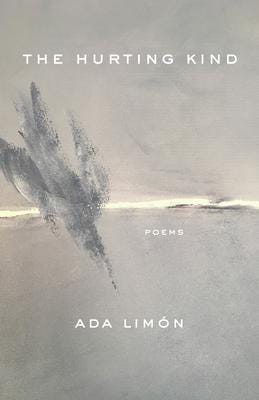

A new book of poems from Ada Limón is always an event to celebrate. I read The Hurting Kind gratefully in one sitting this week, and I look forward to rereading many of these poems over time. On Monday, May 23 at 7 PM Central time, the great Iowa City bookstore Prairie Lights is hosting Limón on Zoom, in conversation with poet Jennifer Knox.

Bookshop of the Week

One of the towns mentioned in When I Sing, Mountains Dance is Camprodon. And gosh does it look beautiful.

Libreria Anglada is the bookshop there, and it specializes in local subjects and nature books.

That’s it for this week. I leave you with maestro Andrés Segovia playing “Leyenda” by the Catalan composer Issac Albéniz. xo Nicie