Dear Reader,

Hello, and a special welcome to new subscribers. And Happy Mothers’ Day!

As the end of the school year approaches in my neck of the woods, I’d like to share with you a book that would be a perfect summer read for a nature-curious young adult, or for a grownup in the mood for a slim and sweet coming-of-age tale set in rural Japan.

Review

The Easy Life in Kamusari

Shion Miura, translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter

Amazon Crossing, 2021

189 pages

$12.95

Despite being in the center of Japan, the language of the Kii Peninsula feels thick in the mouth: warbled, informal. It calls to mind a North Carolinian drawl.

In the middle of a 30-day walk last June, I said hello to an old woman tending her patch, and she replied with the equivalent of, “They done saw a bear o’er yonder—watch yerself.”

Even the A.T.M.s say things that sound like: “Oh hon, thanks for using me, now you come ’round again soon, y’hear?”

I’m always tempted to take out a few extra bucks just to hear more sweet robotic gab.

This delightful snatch of prose is taken from an illustrated essay recently published by the New York Times, a piece by Japan-based writer and photographer Craig Mod entitled “A Long Walk in a Fading Corner of Japan.” Mod, who lives in Kamakura, has engaged in a fascinating artistic practice over the past several years. He walks long distances through rural Japan, documenting the landscape and the culture of a depopulating world, one which despite that fact—or perhaps because of it—nonetheless pulses with life. I remain captivated by Mod’s kissaten project. A kissaten (“kissa”) is the Japanese equivalent of a diner. It’s a coffee shop that doesn’t put on any airs. You can get cheap eats, and smoke as much as you want. Whatever the opposite of hipster is, kissa is it. The opposite of avocado toast is what kissas serve: pizza toast. At one point Mod walked the 1000 kilometers from Kamakura to Kyoto, stopping at as many kissa as he could and chatting with the mom and pop proprietors who feed their small communities, one pizza toast at a time. His beautifully made book Kissa by Kissa is a gesamtkunstwerk of eccentric ethnography.

Prolific novelist Shion Miura’s The Easy Life in Kamusari imagines what might happen when a typical Japanese teenager who has known nothing but an urban, digital, consumerist lifestyle is dropped into just such a rural setting, a community located in Mie prefecture and thus very close to the Kii Peninsula that Craig Mod visits in his New York Times essay. When teen narrator Yuki Hirano introduces himself to the reader, the first thing he comments on is the prevailing dialect and how it reflects the local culture.

Kamusari villagers are really easygoing, especially those living deep in the mountains. They often use the expression naa-naa, which might sound negative but means something like “take it easy,” “relax.” . . . [m]ost of them are involved in forestry, where you have to think in cycles like a century . . . “Running around won’t make the trees grow faster. Get plenty of rest, eat hearty, and tomorrow take what comes”: that seems to be the prevailing philosophy.

Yuki’s parents, worried about their aimless son, have abruptly uprooted him at the suggestion of a guidance counselor, and have enrolled him against his will in a government-sponsored program to train the next generation of forestry workers. Imagine Yuki’s horror when Yoki, the platinum-blond forester who has picked him up at the train station and will be his mentor, snatches away Yuki’s phone and hurls the battery into a mountain pass. “No reception.” Yuki is cut off entirely from the life he has known, and the novel follows him as he attempts to absorb the folkways of his teammates and master the elaborate physical skills of their trade.

Much of the addictive charm of this little book is generated by Miura’s ensemble portrait of the crew that Yuki joins. Yoki, who swings a big ax and an even bigger personality, is the dynamic center. There’s also Seiichi, the wise and confident hands-on owner of an unusually large tract of timber encompassing a mix of old-growth forest and plantation plantings. Iwao and old man Saburo are veterans who round out the squad.

Miura is a veteran of the ganbaru sub-genre of teenage coming-of-age stories, as she has in fact written several, including Run with the Wind (about a pair of running buddies who decide to join an elite ekiden relay team) and The Great Passage (about a crew of brainy misfits trying to complete a dictionary). Ganbaru means “to give your best effort.” Regarding this particular genre, critic Alison Fincher observes: “Persistence takes center stage as characters ‘do their best’ at difficult professions—usually unorthodox ones. Authors carefully lay out the details of obscure or minute crafts as characters fully commit to working hard at them.” This approach lends itself to series extensions, and also to manga and cinematic adaptations. I remember watching the live action film of The Great Passage on an airplane flight to Japan, and enjoying its combination of shaggy characters and tidy plot.

In The Easy Life in Kamusari, the forest itself may well be the real hero. As Yuki relates the story of his apprenticeship year, the four seasons—with their beauties, afflictions, labors, and festivals—each take a turn on the stage. There is no shortage of teen gross-out humor (leeches!), puppy love (a beautiful schoolteacher with a hot hand on the throttle of her motorcycle), and action sequences that allow the characters to encounter the spirits of the forest.

In one of my favorite sections of the book, Yuki relates in great detail just how the men decide in which specific direction they want a tree to fall when it is cut. Each direction has a special name. Yoki is the master craftsman, who never fails to make his cuts such that the tree comes down with the least damage to those around it.

Yoki tapped the trunk twice with the ax handle.

“What does he do that for,” I asked.

“Yoki always does that.” Old Man Saburo smiled. “Before he fells a big tree, he greets the god of the tree. It’s his way of saying, With your permission, I will now chop down this tree.”

The translation by Juliet Winters Carpenter does a fine job of capturing Yuki’s teen voice, the laid-back vibe of the villagers who always have each others’ backs (even if they are now and then at each others’ throats), and the beauty of the place as seen through the city slicker’s wondering eyes. Instead of taking a subway to sit on a tarp in a park and eat pricey takeout, like Japanese urbanites do during cherry blossom season, the villagers of Mie hike up the mountain with homemade bentos to visit an ancient wild cherry tree. Oldsters are carried piggyback style.

“Awesome.” I could barely croak the word out, overwhelmed. The tree had stood for years on this mountaintop, its mossy trunk bending and twisting as it spread its branches to the sky.

. . . Someone spontaneously started dancing; someone else started intoning classical poetry. The atmosphere was free and easy, just as Yoki had said.

Can we humans make our voices chime with the wind that moves through the trees? Can we get what we need from the land without despoiling it? This is a book that offers us the possibility of “yes.” The Easy Life in Kamusari imagines a way of being in which we think carefully about what we want and ask permission before we take it, a way of being that might put our spirits more at ease.

Other Voices, Other Forms

Fans of anime are well familiar with canonical masterpieces by Hayao Miyazaki that are set mostly or partly in the forests of Japan, including My Neighbor Totoro and Princess Mononoke. A lesser-known but highly evocative film is Hoturabi No Mori E (Into the Forest of Fireflies), directed by Takahiro Omoro. This 45-minute anime is based on a one-volume manga of the same title by Yuki Midorikawa. Set in the forests of Kumamoto on the Southern Japanese island of Kyushu, the film follows the young girl Hotaru as she meets and grows close to Gin, a masked supernatural being. As Hotaru grows older, she and her mysterious friend must contend with the limits imposed on their love.

Poem of the Week

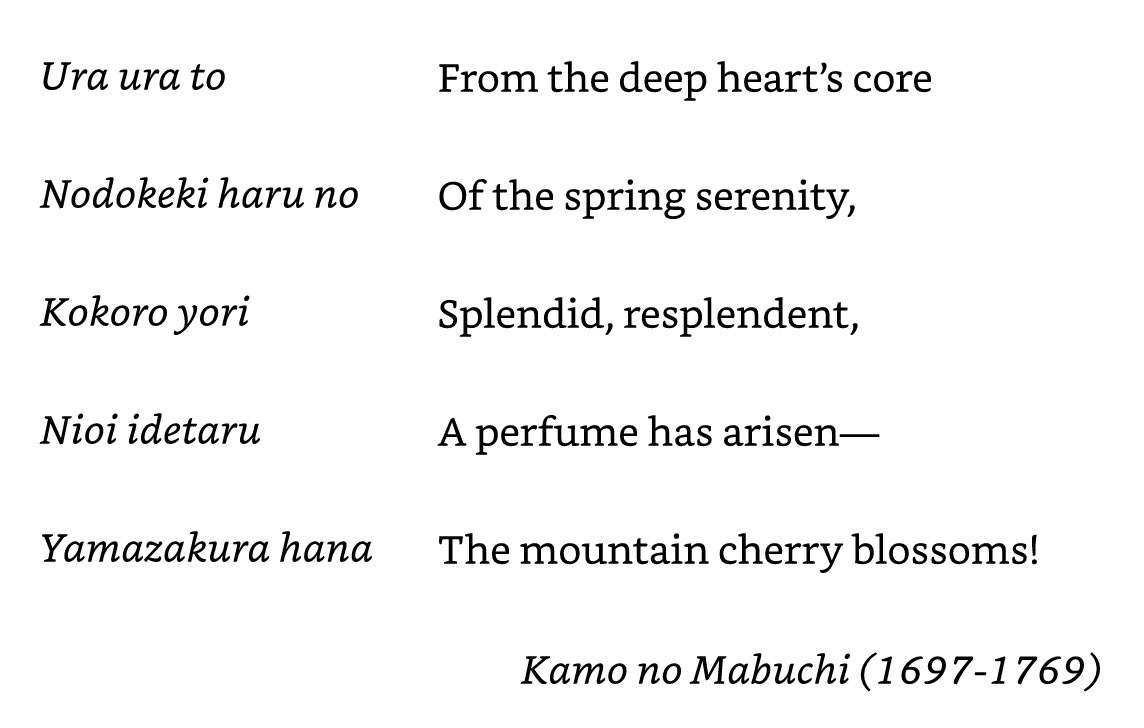

Many works by the great scholar Donald Keene have pride of place in my library. Keene translated this classic poem, which appears in his essential Anthology of Japanese Literature. Kamo no Mabuchi was a key influence on Motoori Norinaga, who championed the concept of mono no aware in Japanese poetry. This term is very hard to translate but it refers the emotions we feel when we have a deep encounter with the fleeting nature of beauty in the living world.

For Your Reading Radar

Kamusari Tales Told at Night is Shion Miura’s sequel to The Easy Life in Kamusari, and May 10 is the publication day for the American edition of its English translation—which I am glad to note was also done by Juliet Winters Carpenter.

For Your Calendar

I recently read and loved Breasts and Eggs by Mieko Kawakami, one of Japan’s leading literary lights. She is currently on a US book tour (to be followed by a UK swing) for her new novel All the Lovers in the Night, the tale of a young writer who decides that she must change her life. This Tuesday May 10 at 6 PM Eastern, Kawakami will be appearing in person at Brookline Booksmith in the Boston area. Details here.

Bookshop of the Week

Though I can’t explain just why, on my my several visits to Tokyo I have yet to visit the neighborhood of Jimbocho, which is famous for its concentration of secondhand bookshops. Kitazawa Bookstore focuses on rare and special editions of books in English. It might have to be my first stop.

That’s it for this week. Be well. xo Nicie

Bam. Homa As they say in Japanese baseball. Thank you for the review. I love the stories of oddballs who find their purpose. I’m writing a novel now about one.