Dear Reader,

Life has been a bit of a flurry since my last post. I ran a marathon in Rhode Island with a dear friend, cheered another on Heartbreak Hill as she ran her first Boston Marathon, co-chaired the Laureate Fellows Awards Panel for the Academy of American Poets (look for exciting announcements about this important program soon), and got on an airplane for the first time in more than two years. Thanks for supporting me in taking a week away.

Also! A warm welcome to new subscribers. The next couple of weeks will be devoted to notes from a book-lover’s idyll in Paris, and then we will probably return to more typical review essays. The chariot often improvises its routes.

I write to you this week from Paris, where Spring is in full force. The chestnuts are in flower, and the first roses are blooming in the garden of the Musée Rodin. Eastern redbuds brighten the corners of the Champ de Mars, and the paths of the cemetery in Montparnasse. I offer you some notes on what may be one of the most splendid libraries you’ve never heard of, and about a fascinating exhibition I was able to see there that speaks to the power of imagination and craft to help us confront the forces of darkness and entropy. This adventure was inspired by one of the great novels of recent years: Piranesi, by Susanna Clarke.

Immeasurable Beauty

I grew up in the era of encyclopedias, and I well remember the promise that everything that could be known was represented there. It was just a matter of knowing how to look it up. We had The World Book, and I loved poring over it. I also remember my fifth grade history teacher Mrs. Dawson (who wore her silvery braids curled with pins on her head) stacking two towers of books to show us how historians weigh evidence, constantly seeking to add to their piles and to determine which argument might be strongest in explaining just why things happened the way they did. Later on, the school librarian taught us to locate books by using the card catalog in the library: pull open the drawers, peruse the cards, copy down the locations, and head to the stacks, where the books next to the one you initially sought might actually hold the key to your project on the Louisiana Purchase. Knowledge became something vast and daunting, a treasure hunt in a vast palace of human memory. The library was a storehouse, but also a portal for exploration and understanding.

When I found myself on the way to Paris this month, I read up on the exhibitions calendar and discovered the Bibliothèque Mazarine, the oldest public library in France, open to scholars since 1643. Now the shared library of the four academies that make up the Institut de France, the Mazarine is named for its founder Cardinal Mazarin, who essentially oversaw affairs of state in France from 1642 to 1661. Look him up. The man was non stop.

The library not only survived revolution and war, but collected aggressively even during periods of disorder, and it now cares for more than 600,000 books and objects. Though you will see few signs from the street, you need merely ask a friendly guard to be whisked into the courtyard of this grand palace on the Seine, free of charge and free to wander up a stone staircase to a suite of reading rooms right out of Harry Potter.

On the day we visited, scholars and members of the public were reading or working quietly on their laptops, as the spirits of French leaders and thinkers presided from their noble portrait busts. Leather dust valances with fringe adorn the shelves and give the rooms a tiny hint of cocktail lounge chic.

Through May 14, the Mazarine is presenting a riveting exhibition about the art and artistic legacy of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778). I was particularly interested to see this show after having read Piranesi by Susanna Clarke, one of the paramount pandemic lockdown reads of 2021. The historical Piranesi was born in Venice—the son of a stonemason, the nephew of an architect, and the brother of a learned priest. He combined these influences with his towering imagination and flair for the dramatic to become the leading engraver of veduti—architectural scenes—of his time.

Piranesi derived fame and income from brilliantly depicted scenes of Rome, especially the ruins of antiquity, and he offered them both to domestic buyers and to the burgeoning market of Grand Tour collectors.

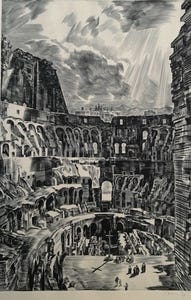

Yet his masterpiece came early in 1745, when he started work on the series Carceri d’invenzione (Imaginary Prisons). Its sixteen striking images depict an array of fantastical, macabre, multi-level environments that appear to be in varying stages of breakdown and disorder. The scales of bodies and architectural elements are often mismatched within images. Hallways, stairs, and ladders appear in bewildering profusion, and often seem to lead nowhere. Elegant sculptures and reliefs stand next to ominous chains and pulleys.

Decay and entropy are at work in Piranesi’s prisons. Large beams are broken in mid-air, leaving jagged, splintered ends. A fire has broken in out in one image. Punishments take place, but with little sense of order or plan. The spaces are both open-air and underground. It’s a world collapsing. Yet the eye is continually drawn upward by the diminishing figures wandering ever higher, to unknowable futures.

Possibly inspired by Piranesi’s contemporaneous work in the theater, the prisons series is a strange and singular testament of the imagination, and the Mazarine’s exhibition does an extraordinary job of documenting its influence on later-century writers and artists, using objects from its own collection as well as loaned works. Thanks to a lecture by Coleridge, Thomas De Quincey found in Piranesi’s work the perfect metaphor for the experience of addiction that he depicted in his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821). Byron’s evocations of Roman ruins have much to do with Piranesi’s scenes and sensibilities. Victor Hugo and Théophile Gautier—and later Baudelaire— championed Piranesi. Gautier wrote:

Seized with religious dread, we furtively traversed these immense Piranesi-style palaces, following the maze of corridors, the convolutions of stairs that penetrate the chasms and soar into the heavens.

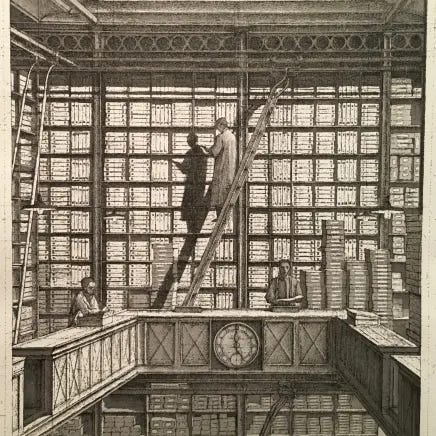

As we move closer to the present day, Piranesi was undoubtedly an inspiration for the Dutch artist M. C. Escher (1898-1972). The Mazarine has chosen to highlight two other modern masters of printmaking: Albert Decaris (1901-1988) and Erik Desmazières (1948- ). Decaris used beautiful ink-wash techniques in his engravings, to great effect.

Desmazières has employed dazzling technical skill to create fantastical worlds filled with just as much mystery as Piranesi’s, though they also suggest a greater sense of lightness and possibility. In some respects, the work of Desmazières was for me the greatest discovery from this show.

This is where Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi comes in. Her hero, none other than Piranesi, finds himself in “The House.” But The House—a ruin, a prison, a site of exile, with its ominously rising tides (reminiscent of the acqua alta of Venice, and now of so many other cities)—is also a kind of paradise, in which friendship and enmity traffic strangely with each other, and in which the never-ending efforts to map the structures of the world, to understand its birds and weather, are their own reward. For more, you might consult Ron Charles’ review in The Washington Post. I leave you with a few words from Clarke’s character Piranesi: “The Beauty of The House is immeasurable; its kindness infinite.” Happy Earth Day.

Other Voices, Other Forms

For a vintage taste of Anglo-Francophone comity with a dash of comedy, please enjoy “For Me Formidable” by Charles Aznavour.

And with a nod of the beret to Charioteer Deborah Rubinstein, who lives in Paradise, I mean, Paris, here’s a more recent lovely bit of Franglais singing with a love-among-the-ruins feel from the chanteuse Christine and the Queens.

Bookshop of the Week

Any visit to the Bilbliotheque Mazarine should be capped with a browse at the Institut de France’s bookshop, Librairie des Immortels. Members of the Académie Française are known as Les Immortels.

Jusqu’à la semaine prochaine. xo Nicie

Lovely writing. If I ever have a few free weeks, there are some libraries in Paris that I’d love to conduct music manuscript research. Enjoy!!!!