Issue 48 — As When Obliterating Fire Rages

Four Notes on The Iliad by Homer, translated by Caroline Alexander

Dear Reader,

After last week’s conference in Philadelphia, I drove on to Washington DC, to visit my daughter and see her apartment and neighborhood for the first time since she moved there last year. Spring has already come to Washington, and the cherry blossoms were at their peak. A snap of chilly weather was keeping them going.

I grew up in DC, and it was quite a thrill to go running past the Tidal Basin, across the Potomac, and around my childhood neighborhood. Sometimes it’s the little continuities that mean so much. Scheele’s Market is still going strong, with a clock that doesn’t work, a jar of dog biscuits on offer, and a handmade sign in hues of blue and yellow: “No War!”

As I ran past the last house my family lived in, I saw a dumpster out front. It was jarring to see period doors and woodwork that I’d known so well being tossed out like junk. I remember the pleasure my mother took in asking me to help her pick out wallpapers. She loved the intricate patterns and wild color palette of the Arts and Crafts movement. I’m sure all that is gone as well, or will be soon.

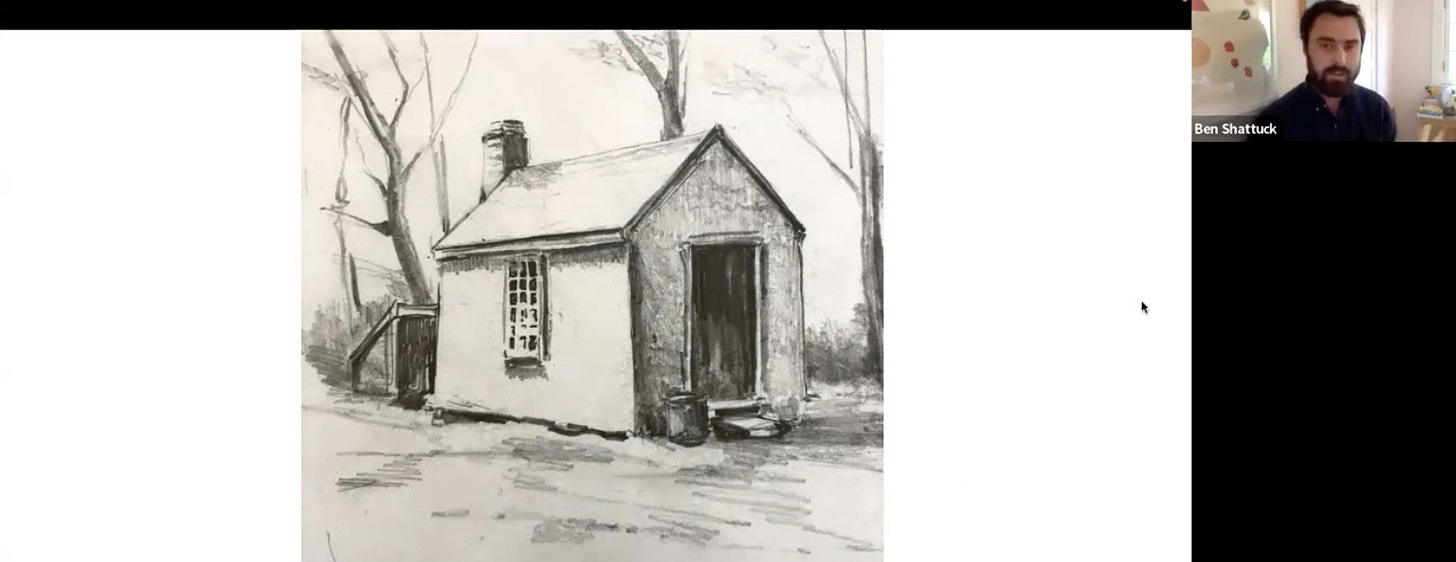

Last Sunday we had a truly great ThoreauDown on Zoom, to celebrate both Spring and Frugal Chariot’s first birthday. Sincere thanks to Ben Shattuck, Megan Marshall, David Foster, and Hannah Harlow — for sharing their words, their stories, and their appreciation for Henry, that eloquent oddball with unusual moral clarity. And thanks to all who attended and joined in the fun. Here is Ben reading, along with his sketch of the replica of Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond. If you couldn’t join us, you can replay the session on YouTube (though please note that I forgot to start recording until after I’d given my introduction).

I will be writing about Ben’s new book Six Walks: In the Footsteps of Henry David Thoreau a bit closer to its publication date, which is coming later this month. This week, I would like to share a few thoughts about The Iliad and the Anthropocene.

Four Notes on The Iliad: Three Women, Five Wars

The Iliad

Homer

A New Translation by Caroline Alexander

HarperCollins, 2016

608 pages

$19.99

When she was a teenager, Caroline Alexander read part of The Iliad for the very first time, after a swim practice. She let the names and terms she didn’t know slide by, and simply allowed the story to gather her up and sweep her away. Alexander went on to study classics, and early in her career she set up a classics department at a university in Malawi. Years later, she returned to report on the murder-conspiracy trial of Malawi’s classics-obsessed former dictator Hastings Banda. She found that one of her former students was his defense attorney, and he said to her, “Professor, you told us that careful study of the classics prepares a person for anything they might face in life.” Immersion in the classics certainly helped prepare Alexander to become the author of best-selling historical epics, including Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty and The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition.

In the 2000s, Alexander’s attention returned to The Iliad as America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan unfolded, with their devastating death tolls ever mounting. She immersed herself in recent scholarship on the work, and then began to translate it into English. In 2010 she published a book-length commentary on the poem, entitled The War That Killed Achilles: The True Story of Homer’s Iliad and the Trojan War. She followed that in 2016 with The Iliad: A New Translation by Caroline Alexander. Alexander’s central insight is that too often The Iliad is taught and discussed as a “poetic metaphor for the human struggle and experience,” when it is in fact primarily about warfare.

The Iliad is is riveted on what may be called the enduring realities of war: the fact that an individual warrior must risk his life for a cause in which he does not believe, or must subject himself to the command of a lesser man; or that a successful warrior needs not only skill, but the good luck of being loved by the gods — and that these same gods are fickle, and the outcome of any combat mission is therefore fraught with mortal uncertainty; above all that war blights every life it touches.

Alexander’s reporting on Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with traumatic brain injuries (for National Geographic) speaks to her depth of commitment in bearing witness to the ravages of war, past and present.

The Blight

The Iliad tells the story of the ninth year of a ten-year conflict. Neither the beginning nor the end of the war (with its famous mechanical horse) are recounted. The initial conflict is within the Greek ranks: Achilles, their greatest warrior, is challenging the vain and shallow leadership of Agamemnon. Achilles has the prestige to upbrade Agamemnon and refuse to fight. A rank-and-file solder who tries to make the same argument is cudgeled by Odysseus. That man retreats whimpering, a bloody welt springing up on his back. In the early going, the poet focuses his attention on these moments of truth-telling insubordination, and of possible deescalation — moments that might have led to peace, but do not.

There is a strong argument for reading these 15,693 lines steadily from start to finish, completing a portion each day. The range of wounds and sufferings, the scale of the slaughter, and the numerous micro-obituaries pile up in the reader’s consciousness. Tendons are severed, brains spew out of skulls, bodies hit the earth hard. The killing sprees rage on in sections of unbearable length, reminiscent of a Quentin Tarantino film. The reader is constantly prompted to ask herself: what is the point of all this? As Achilles himself puts it to Odysseus:

. . . But why must the Argives be at war with the Trojans

Why did the son of Atreus assemble and lead and army here? Was it not for Helen of the lovely hair?Do the sons of Atreus alone among mortal men love their wives

No, for any man who is decent and wise

Loves her who is his own and cares for her . . .

The poem lays bare the raw truth that war is initiated by the powerful, either justly or unjustly (or in some combination of the two), on the basis of their judgements of right and might. Whether just or unjust, war unchains the dehumanizing and chaotic forces of mass violence. In 1940, shortly after the fall of France to the Nazis, Simone Weil (1909-1943) published a long essay (later translated by Mary McCarthy) entitled “The Iliad, or The Poem of Force.” Weil called the poem:

the purest and loveliest of mirrors.

To define force — it is that x that turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing. Exercised to the limit, it turns man into a thing in the most literal sense: it makes a corpse out of him.

The blight of force extends to the women on both sides of the conflict. Andromache runs a hot bath for her husband Hector, only to learn of his death. She fears, correctly, that in the event of a Trojan defeat, fate will bring slavery or death for herself and her child. Weil notes that the enslaved women who serve Achilles wail in mourning for Patroclus, but also “for their own torments.”

Suppose a Smelter, Imagine a Broodmare

Homer depicts the material needs and tools of the fighters with remorseless clarity.

Let each man sharpen his spear, let him get his shield at the ready

Let him feed well his swift-footed horses.

And when he has inspected his chariot, let each man turn his attention to war.

He lavishes attention on personal armor. Achilles’ mother, the goddess Thetis, goes begging to Haphaestus, blacksmith of the gods, for a new suit of armor for the son she knows will nonetheless die soon.

In The War That Killed Achilles, Alexander reminds us that American soldiers in Iraq often had to purchase urgently needed protective equipment on their own, funded by family bake sales back home.

A fascinating aspect of The Iliad is that although we do see Hephaestus forging an extraordinary new shield for Achilles, the bronze itself — the material that generates the lethal piercing and slicing weapons, as well as the protective gear — seems to appear by magic. We know that the ash wood that makes the best spear handles comes from Mt. Pelos. Yet we never hear about the miners and their mines, or see the great forests or meet the Pelian loggers. Similarly, we never encounter the farmers and herders who are generating an apparently inexhaustible supply of livestock to be slaughtered for food and sacrifice, or to be whipped and driven into combat. In one episode, two horses become so distraught on the battlefield that they refuse to move, provoking dreadful lashings. Imagine their mothers, their foals.

Martin Puchner, Professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard University, has recently published a book titled Literature for a Changing Planet. Puchner suggests that we might read to note the ways in which the extraction and exploitation of non-humans is deeply embedded in canonical narratives. An implicit assumption of the heroic mode is that there is a never-ending supply of resources to sustain the lifeways and conflicts of the elite — and that lower-status humans will accomplish the difficult and dangerous work of transforming raw materials into tools and fuels and food.

The River’s Resistance

It could be the work of a lifetime (and has been for many) to think about the roles of the gods in Ancient Greek life and literature. What do they control? What is beyond their control? What motivates them? If not unlimited, their agency is certainly potent. On this recent reading of The Iliad, the episode that struck me with greatest force was a section of Book 21. In one of the epic’s most pitiless war crimes (see also the twelve Trojan POWs executed to feed Patroclus’ funeral pyre), Achilles, returning to combat to avenge the death of his comrade Patroclus, has just murdered Priam’s son Lykaon, unarmed and begging for mercy. Lykaon had returned home only twelve days earlier (the miserable specificity of that number), after having been captured and sold into slavery years before — by none other than Achilles. Achilles goes on to kill Trojan after Trojan, their bodies clogging the river. Suddenly the god of the river, Scamander, appears in human form, enraged and shouting:

. . . my lovely flowing waters are full of corpses,

Nor is there any place where I can pour forth my stream into the bright salt sea

Crammed with corpses; your killing is annihilation.

Come and let me alone; I stand aghast.

Scamander, in an act of self-defense, and with help from the neighboring river Simoeis, assails Achilles with torrents of water. The poem courses with the outrage of the river chasing the mighty warrior.

He kept leaping, his feet high

His heart harried with fatigue; but the torrential river overwhelmed his knees’ strength

As it poured under, eating away the earth beneath his feet.

Achilles wails, “now it is my fate to be taken by a mean death . . . like a swineherd boy.” If not for the subsequent intervention of his immortal backers Poseidon and Hera, Achilles would not have lived to face Hector. Reading today, Scamander’s flood represents an extraordinary act of ecological testimony and self-defense, in the face of man’s ravages. The wild flood fills the plain with floating corpses and gear. Other gods show up to pitch in and help with the recovery. This passage is a notable illustration of Alexander’s approach to the challenge of translating the text. Rhythms are strong, and the language is clear — but at the same time high-flown enough to capture the nobility of the quasi-mythic struggle being depicted.

As When an Obliterating Fire Rages

Writing as a refugee during World War II, the Ukrainian philosopher Rachel Bespaloff (1895-1949) argued that the epic has a clear moral center of gravity. Achilles is an amoral avenger, drawn back into a pointless war, while Hector is a resistance hero. As quoted in Christopher Benfey’s insightful introduction to a dual edition of Weil’s and Bespaloff’s essays, Bespaloff writes:

In the crowd of mediocrities that are Priam’s sons, he stands alone, a prince born to rule . . . Neither superman, nor demigod, nor godlike, he is a man and among men a prince . . . Loaded as he is with favors, he has much to lose . . . Apollo’s protégé, Ilion’s protector, defender of a city, a wife, a child, Hector is the guardian of the perishable joys.

It is hard not to think of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky when reading Bespaloff’s words.

Like any great narrative, The Iliad offers moments of slowness and suspension. Priam’s embassy to Achilles to beg for Hector’s body is perhaps the most moving. Bespaloff remarks on “those moments of contemplation, when the spell of Becoming is broken, and the world of action, with all its fury, dips into peace.”

In smaller ways, Homer’s extended similes are also a crucial technique for slowing things down, and for invoking the world beyond the battlefield. Early in the poem, after some of Athena’s trademark rousing, the Greeks array themselves for battle.

As when obliterating fire rages through an immense forest,

on the mountain height and from afar, the flare shows forth

so the gleam from the sublime bronze of marching men

glinting through the clear sky reached heaven.

The heavens are filled with satellites now, nodes in a geo-strategic panopticon that keeps constant watch on our doings. Like gods arrayed on the slopes of Olympus, they see the armored vehicles moving, they see the explosions flaring forth. They see the buildings and fuel tanks on fire, spewing poisonous gases into the atmosphere like the forests that now burn and burn. The satellites see the rivers filled with debris from blown-up bridges. Maybe it would take a drone to see the people, fighting and fleeing, catching rainwater, finding food for their pets. And perhaps it would take a poet to see, to really see, the people — in all their fear and all their courage — prepared for anything they have to face in life.

Other Voices, Other Forms

Sviatoslav Richter was born and raised in Ukraine, and went on to live most of his life in Soviet Russia. For me his recordings are music in its purest form: the notes flow like the clearest stream. Here is a lapidary performance of both books of J. S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier.

Poem of the Week

The Triumph of Achilles

by Louise Glück

In the story of Patroclus

no one survives, not even Achilles

who was nearly a god.

Patroclus resembled him; they wore

the same armor.

Always in these friendships

one serves the other, one is less than the other:

the hierarchy

is always apparent, though the legends

cannot be trusted--

their source is the survivor,

the one who has been abandoned.

What were the Greek ships on fire

compared to this loss?

In his tent, Achilles

grieved with his whole being

and the gods saw

he was a man already dead, a victim

of the part that loved,

the part that was mortal.

For Your Reading Radar

Climate journalist Doreen Cunningham has written a compelling memoir entitled Soundings. In the wake of her divorce, Cunningham and her son set out to follow whales on their migrations. The Guardian has praised Cunningham’s “sensuous descriptions,” and says the that book’s questions “simmer, tantalizingly.”

For Your Calendar

This is a little bit “meta,” but I do love books about bookstores. On Monday, April 11th at 7 P.M. Eastern, Jeff Deutsch of the great Seminary Co-op Bookstores in Chicago will be appearing in conversation with Shuchi Saraswat (via Harvard Bookstore), to discuss his new book In Praise of Good Bookstores. Details here.

Bookstore of the Week

Lexikopoleio looks like a cozy spot to look for a book in Athens. It’s close to the National Garden and the Lyceum of Aristotle. Good looking tote bags, too.

Be well. xo Nicie