Dear Reader,

I can confirm that blizzards are good weather for writing. After a hectic week, I’m camped out by the wood stove with Kenji the cat, watching the white world outside: plants shuddering, snow whizzing by horizontally.

When I traveled to Scotland in November of 2019, I made a special trip to hike in the Cairngorms, because I had been so inspired by this week’s book. The photographs included below were taken then, and I will post a piece about that journey for paid subscribers this coming week.

Review

The Living Mountain

Nan Shepherd

Canongate Books, 2019

126 pages

$22.00

The writer always writes in historical time, but it is not always her luck to write for her own time. How else to explain Nan Shepherd’s decision in 1945 to put the manuscript of The Living Mountain into a drawer, after the first editor to whom she showed it turned it down? She didn’t revisit the idea of publication for more than thirty years. Shepherd, a successful Modernist poet and novelist throughout the 1930s, had a serious track record, and she should have had a ready audience waiting after the war. Surely the faintly patronizing reaction of her colleague Neil Gunn and the single rejection should not have discouraged her as much as they apparently did. Perhaps she worried that this prose tone poem about the Cairngorms mountains in the Scottish Highlands would feel quaint or beside the point to readers living through the final cataclysms of World War II and its aftermath. In the age of Orwell, Sartre, de Beauvoir, Koestler, and Steinbeck, the most urgent questions perhaps had to do with what damage humans were capable of doing to each other, and whether there was a path forward.

Whatever the facts of the matter, we can only be grateful that Shepherd (1893-1981) did finally arrange for the publication in 1977 of these incomparable essays about her experiences of walking those high hills, over decades. We might catch a hint of vindication in her tone when she writes in the Foreword, “Now, an old woman, I begin tidying out my possessions and reading it again I realise that my traffic with a mountain is as valid today as it was then.” Her choice of the word “traffic” fascinates. While “traffic” mainly conveys the sense of “dealings” to readers of English, it also carries a hint of the inevitable disturbance that humans bring. Yet in Scottish Gaelic, “traffeck” means familiarity, and also friendship. That last connotation may explain why this book has exerted such a hold on so many readers. The Living Mountain is not only a brilliant depiction of the Cairngorms, it is also a portrait of Shepherd’s ardent relationship with these mountains, as well as her search for truth.

The Living Mountain can be divided into two parts. In the first six chapters, Shepherd describes the inanimate aspects of the landscape: the terrain (“One does not look upwards to spectacular peaks but downwards to spectacular chasms”), the streams and lakes (“They are elemental transparency”), the seasons (“Water running over a rock face freezes in ropes, with the ply visible”), the weather (“To walk out through the top of a cloud is good”). Even in these early chapters, she foregrounds not only the challenge of finding language adequate to perception, but also the difficulty of perceiving fully all that exists in the world. She encourages the reader to look at the landscape backwards and upside down, by physically turning away from the scene, bending over, and looking at it through the legs.

How new it has become! From the close-by sprigs of heather to the most distant fold of the land, each detail stands erect in its own validity. In no other way have I seen of my own unaided sight that the earth is round . . . the focal point is everywhere. Nothing has reference to me, the looker. This is how the earth must see itself.

This moment of stringent clarity is to be found on page 11, and there is something like it to be discovered on nearly every page. Critic Nicholas Lezard got down to brass tacks when he reviewed a paperback edition of the book for The Guardian. “To intrude a note of coarseness, £10 might seem a lot for a book barely over 100 pages long. But it's not: it's over 1,000 pages long, because you are going to read it at least 10 times – and find something different in it each time.”

Shepherd devotes the second half of the book to the lifeforms of the Cairngorms (plants and animals, including humans), and to modes of human experience. She is brilliant, for example, on what it is like to sleep in the open. And she is dedicated to engaging her senses to the fullest.

Birch . . . needs rain to release its odour. It is a scent with body to it, fruity like old brandy, and on a wet warm day, one can be as good as drunk with it . . . Exquisite when the opening leaves turn them to a golden lace, they are loveliest of all when naked. In a low sun, the spun silk floss of their twigs seems to be created out of light.

The exquisite balance of the book is that Shepherd can be “as good as drunk” with the beauty of the Cairngorms, yet without being sentimental. She is honest about the rain, funny about the midges, and rueful about human depredations of the land and its wildlife. She can revel in solitude without illusions of the pristine.

Perhaps the greatest gift of this book is the manner in which Nan Shepherd constantly probes our human purposes, and our connections to the ongoing and infinite world around us. What should we be looking for when we exert our bodies up steep slopes? Yes, for the “tang of heights” and the attaining of summits—but not primarily for those achievements.

Often the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination, when I reach nowhere in particular, but have gone out merely to be with the mountain, as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him.

Or, as she closes her Foreword to the book, “That it was a traffic of love is sufficiently clear; but love pursued with fervour is one of the roads to knowledge.” If the most urgent questions for our time are what damage humans are doing to the environment and whether there is a path forward, that might explain the current fervor for this not just valid, but essential book. Nan Shepherd may not have had the luck to have been heard aright in her time, but it is our good fortune that her writing comes down to ours.

Other Voices, Other Forms

It is rare for an elderly woman to be the hero of a film, and even rarer for that character to be a mountain climber. At the age of 83, actress Sheila Hancock took the title role in Edie, playing a woman who is determined to climb Suilven, one of the most technically challenging mountains in Scotland. In this short video, Hancock and the crew tell the story of how the film was made. It is currently available to stream.

Poem of the Week

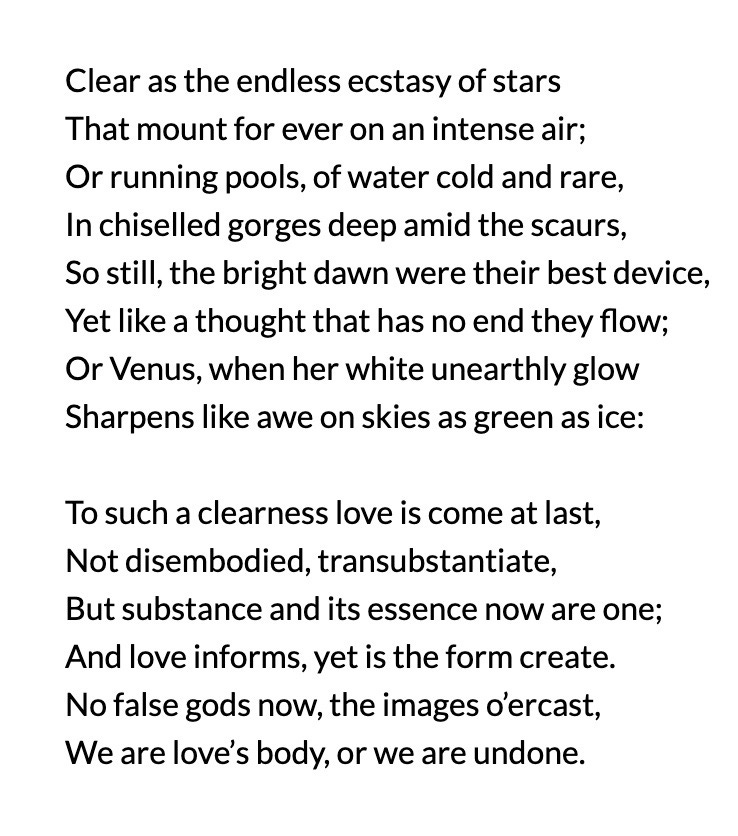

I do recommend In the Cairngorms, a slim collection of poems by Nan Shepherd. Here is “Real Presence” via the wonderful Scottish Poetry Library.

For Your Reading Radar

The Cairngorms are featured in Time on Rock by British rock climber Anna Fleming, which was released in the UK last month. This book, also published by Canongate, “is Anna's journey of self-discovery, but it is also a guide to losing oneself in the greater majesty of the natural world. With great lyricism she explores how it feels to climb as a woman, the pleasures of the physical demands of climbing, fear and challenge, but more than anything, it is about a joyful connection to the mountains.” The book’s US publication date is in May.

For Your Calendar

On February 25th at Noon Pacific time, the prolific British writer Adam Nicolson will be in conversation with author Nathaniel Rich, via Point Reyes Books. Nicolson’s new book, Life Between the Tides, is an exploration of the life that teems in the rockpools at the edge of the ocean. Details here.

Bookshop of the Week

You might launch off for the Cairngorms via Edinburgh, and if you do you must visit Toppings & Company. This splendid shop offers one of the best browses you’ll ever find. Tea and coffee are on offer, the seating is comfy, and pets are welcomed.

That’s it for this week. Wherever you are, stay cozy! xo Nicie

Cover Photo: by Myrrddin Irwin, Braemar, 2019.