Dear Reader,

Greetings and salutations. We’ve had a warm-up here, and the daffodils are getting ready to roll. We planted a lot of them last Fall, fearing that lockdown would be protracted and knowing that we’d need something to look forward to. We weren’t wrong.

This week we move to themes of human ecology, and of place and displacement, as the global community marks the tenth anniversary of the Great East Japan Earthquake of March, 11 2011 and the triple disaster that ensued: earthquake, tsunami, nuclear accident. I have been fortunate to visit Japan a number of times over the past fifteen years, and it is a country I dearly love.

When in Tokyo, I stay in an AirBnb on the top floor of a house in Shibuya, hosted by a very kindly couple. I usually go running in Yoyogi Park, and it is there that I first saw a camp for Japanese people without homes, very quiet and neat in the woods at the back of the park, near the area where children learn to bike. When I learned that Yū Miri’s novel, Tokyo Ueno Station, is about a man living in a Tokyo homeless camp, I had to read it. Homelessness is actually rare in Japan: perhaps fewer than 10,000 people these days have no permanent home, compared with approximately 600,000 in the U.S. But all societies have members who struggle to belong and to survive the tribulations of life. I am glad to share with you my thoughts on one of the most layered and lyrical explorations of loss and displacement that I have ever read.

Review

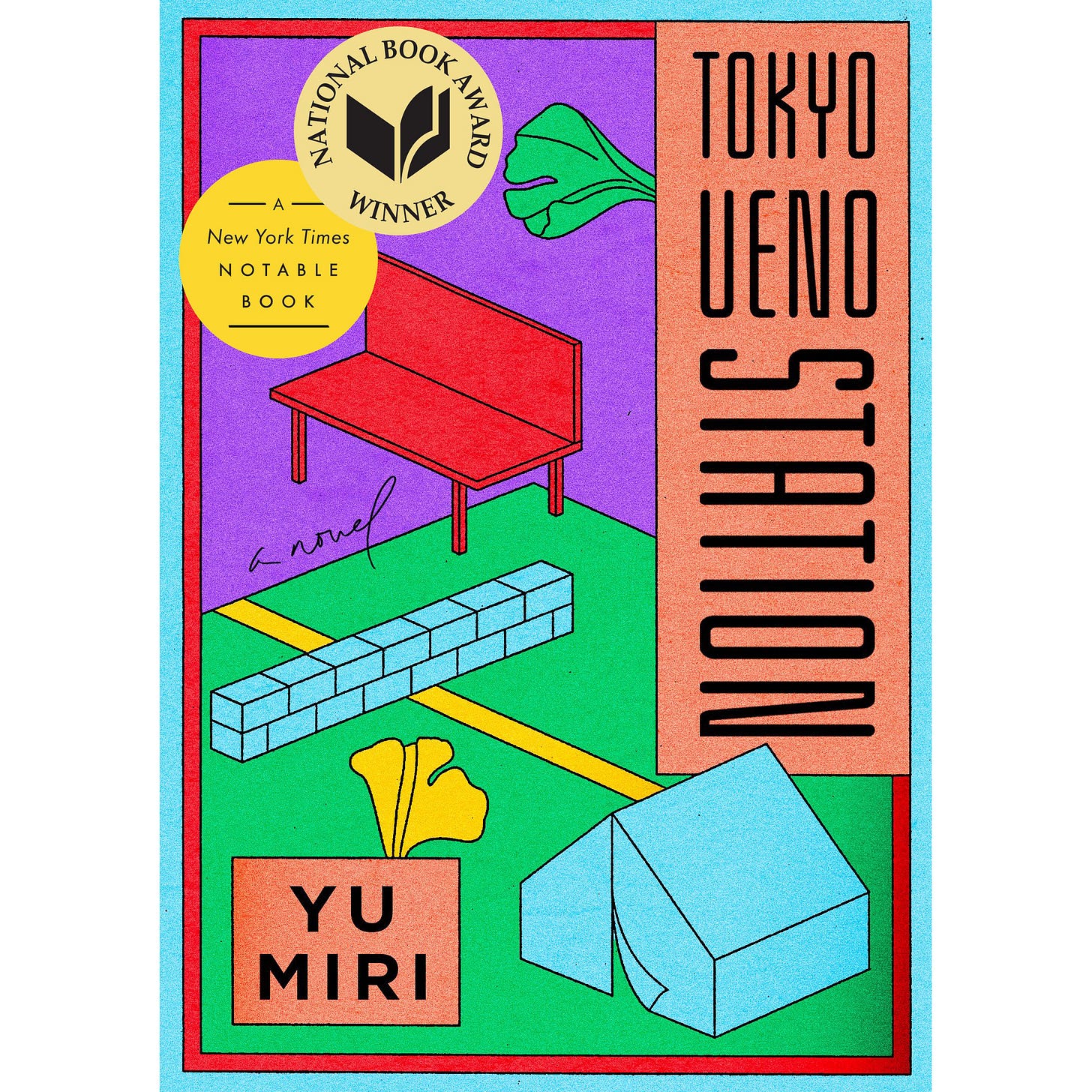

Tokyo Ueno Station

Yū Miri

Translated by Morgan Giles

Riverhead Books, 2020

180 pages

$25.00

Can we all agree on the right to despair? It seems a simple thing for us to acknowledge that the sorrows of this life may simply be intolerable. And yet the machinery of our social, economic, and religious institutions so often rejects despair as an input. The system reacts with messages like “Never give up!” and, in a slightly more sympathetic tone, “Time heals all wounds.” Or, as if it might be time to change the subject, “This too shall pass.” Of course, the machinery is us. We say these things. And while such nostrums may be helpful on many occasions, they sometimes amount to an invitation for the grief-stricken to tamp down their despair, and to do something more useful and less disruptive to the rest of us.

Korean-Japanese writer Yū Miri is no stranger to despair. The child of Korean War refugees, Yū was cruelly bullied and eventually expelled from school in Yokohama, where she spent her childhood. She struggled with suicidal impulses. Now the author of more than twenty books and plays, Yu has said, “I write for the people who don’t belong anywhere.” But where do you go when you don’t belong?

Tokyo Ueno Station is a very specific and important place in Japan. It is a major railway hub, the “Gateway to the North,” where commuters and long-haul travelers catch trains to the northern region of Tōhoku, and the island of Hokkaido beyond it. The Ueno district is a cultural capital within the capital, home to Tokyo University, several museums, a zoo, and a large park. Ueno Park is one of the most famous sites in Japan for hanami: cherry blossom viewing, and the festive picnics that go with it. All very Instagrammable.

In Tokyo Ueno Station, her small, powerful novel of overwhelming grief, Yū Miri reminds us that the area is also a destination for the despairing, and for the dead. The park includes an ancient burial mound from around 400 CE, as well as a nineteenth-century battleground. It was to Ueno Park that many thousands of terrified Japanese fled during the great Kantō Earthquake and Fire of 1923. Ueno is the site of a mass grave for nearly ten thousand victims of the American firebombing of Tokyo in 1945—a raid that claimed more than one hundred thousand lives in total. In recent decades, and especially during periods of economic stress, the area around the station has served as a major encampment for people without homes.

And so it is that Ueno, painstakingly described in both historical and quotidian detail, is the place where our protagonist Kazu goes to live in the homeless camp. It is here that he dies, and then returns as a restless ghost. In developing Kazu’s story, Yū drew on many conversations she had shared with residents of the Ueno Park camp. She also conducted numerous interviews with displaced residents of Fukushima, where she began spending time after the 3/11 disasters.

Born in 1933 to a farming family in Tōhoku, Kazu grows up poor. His forebears had migrated from Japan’s western coast to its eastern coast, where they were ostracized for the Pure Land strain of Buddhism that they practiced. Kazu’s family persists through desperate conditions after the war, constantly at the mercy of loan sharks and repo men. He drops out of school as a teenager in order to work to support his family—and work he does, ceaselessly. Over decades, Kazu toils at construction sites in Tokyo. He clocks every possible hour, lives in a boarding house, and sends as much money as he can back to his wife Setsuko, who farms and raises their two children, Yoko and Kōichi. He sees his wife and children only twice a year.

Kazu and Setsuko are among the millions of working class citizens who literally rebuild war-ravaged Japan, at the cost of great personal sacrifice. And just when they have attained some measure of economic stability, and have managed to see that their children are educated for professional careers, comes a tragedy. Kōichi, who has just qualified to become a radiologist, is found dead of unknown causes at the age of twenty-one.

In a powerful extended sequence, we share Kazu's experience of his son’s death and funeral in Minamisōma, outside of Fukushima. This poor man has lost his only son before ever having the chance to know him. Time breaks down for him, even as the death rituals continuously unfold. Kazu is undone.

Before, I used to wake up, think about where I was, what I was doing, what day it was, then open my eyes, but afterward I was woken up by one fact alone: Koichi was dead. The fact that my only son was dead kept me from sleeping every night, and when I did nod off, exhausted, it broke through my sleep every morning like a kid smashing a baseball through my window . . .

I was overwhelmed by an emotion, one that I was so tired I could not place. I was exhausted, yet I was still tensed. My whole body was on guard against my emotions. I could not bear it, no more, I could not bear to be sad, to suffer, to be angry—

The funeral section of Tokyo Ueno Station is a braid of experience, memory, and prayer. Pure Land Buddhism is anchored in a single prayer of faith and gratitude, “Namu Amida Buddha,” which is chanted over and over as the means to salvation. This prayer, called the Nembutsu, is woven together with Kazu’s sensations and memories, creating a kind of fugue. Morgan Giles’ translation is quiet, spare, and compelling. Tokyo Ueno Station was awarded the 2020 National Book Award for Translated Literature.

In a conversation on Twitter this week about literary funerals, Dr. Rosie Reynolds, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on Woolf, brought up Mrs. Pargiter’s funeral in The Years. The words of the Anglican funeral rite move in and out of Delia’s consciousness, but ultimately fail her.

“We give thee hearty thanks,” said the voice, “for that it has pleased thee to deliver this our sister out of the miseries of this sinful world—

What a lie! she cried to herself. What a damnable lie! He had robbed her of the one feeling that was genuine; he had spoilt her one moment of understanding.”

In a parallel fashion, Kazu experiences Kōichi’s funeral rites but is unconsoled. Such rituals develop to keep the bereaved integrated within the community, and to provide structure and meaning to death. Yet comfort is not always to be found in faith, or even in family. What then?

NAMU AMIDA BUTSU

NAMU AMIDA BUTSU

NAMU AMIDA BUTSU

NAMU AMIDA BUTSU

I carried the funeral tablet and walked at the head of our short procession to the hearse.

Around here when a son is born, we congratulate the parents by telling them that now they have someone to carry their funeral tablet. “What, this kid?” People say, laughing in response.

I had lost my tablet carrier.

I was the one who carried his tablet.

NAMU AMIDA BUTSU

NAMU AMIDA BUTSU

My hands . . . my feet . . .

My hands carried the tablet, my feet walked toward the hearse.

I had hands and feet, but there was nothing I could do.

NAMU AMIDA BUTSU

NAMU AMIDA BUTSU

Overwhelmed by grief, the grief that had taken everything from me . . .

The gift of this deep intimacy with Kazu at the time of Kōichi’s funeral is that as readers, we are prepared to understand Kazu’s response when he suffers a second terrible loss. Kazu is the victim of so many forces beyond his control, and of the failings of his society. But he is not merely a pawn on capitalism’s chessboard. He’s an admirable person and a canny observer, someone you want to be with. He makes a series of difficult and honorable choices throughout his life, and lives with dignity in the homeless camp, where he meets the enigmatic and erudite Shige. This character is the novel’s voice of history, and an affectionate caregiver to Emile the cat. The passages about Kazu’s life and afterlife in the park are lapidary.

The three sparrows that were perched on the lamppost before have now gone. I am haunted by this day, today, and regardless of what I am now, I would like to exchange a glance with someone, anyone, even a sparrow.

Structurally, Tokyo Ueno Station is a complex clockwork, and I marveled at the gears and springs. Kazu’s life carries a series of coincidental yet intimate connections to Japan’s Imperial Family, which speaks to the fundamental injustice of his situation. (Indeed, the callous clearing of the camp by officials to make sure the homeless aren’t seen by members of the Imperial Family when they come for a visit is a pivotal moment for Kazu. And it seems to foretell the clearing of the park that has apparently taken place in advance of the 2021 Olympics.) The book jumps back and forth frequently in time. And we eavesdrop with Kazu on a range of everyday people in Ueno. They trade banalities while passing by Kazu and his homeless neighbors, without a glance or a kind word. At times it can be hard to know whether Kazu is alive or is a ghost. But perhaps that is the point. We tend to treat people who are experiencing displacement and poverty as if they don’t exist. We too stroll by as they do, talking of family dramas, food preferences, and bourgeois irritations.

“Anyway, she’s always snacking on something—chocolates or sweets.”

“They say you really shouldn’t overdo it with chocolate.”

‘Everything in moderation. I mean, I eat sweets, you know. Six sticks of strawberry Pocky is my limit, though . . .”

We say these things.

The U.S. hardcover edition of Tokyo Ueno Station, published by Riverhead Books, just might be a perfect book. It is small and rests quietly in the hand. It uses two main fonts that carry on an interesting conversation with each other. And it has a beauteous cover by Lauren Peters-Collaer that combines elements of Kazu’s life in the park—bench, tent, chrysanthemum, ginkgo leaf—rendered in brightly colored, stylized shapes. One of the tent flaps lies open in what feels like a welcoming gesture. Yū Miri has welcomed us into Kazu’s life, a life of boundless, restless sorrow—as was his right. It is a life that glows beyond its end, as the novel arrives at a tragic and visionary conclusion that encompasses the Great Triple Disaster of 2011.

The yellow of the ginkgo leaves poured into my eyes like paint dissolving into water. Each leaf had a golden glow that was almost too beautiful—the ones that danced in the air, the soggy ones trampled on by people, and the ones that still stuck to their branches . . .

My vision was filled with yellow leaves, whirling in the winter wind. The turning of the seasons no longer had anything to do with me—but still, I didn’t want to take my eyes away from that yellow, which seemed to me like a messenger of light.

Words and Images

Yū Miri moved to Fukushima full-time in 2015 and opened a bookstore/cafe called Full House, with an adjacent community theater space, in a part of Minamisōma called Odaka. Odaka currently has 3,700 residents, about 30% of its 2010 population. Here you can watch and hear her read from Tokyo Ueno Station.

The Triple Disaster inspired many great Japanese artists to make work in Tōhoku. In 2016, the MFA Boston held an exhibition called In the Wake: Japanese Photographers Respond to 3/11. I am especially taken with the work of Arai Takashi, who makes daguerrotypes. Here is his “Radioactive Lily Study,” from the series he made in and around Fukushima in 2012.

Every day, Arai posts a daguerrotype to his Instagram feed, Daily_Dag.

NHK is presenting many programs related to the 10 year anniversary of 3/11. I especially enjoyed this touching documentary about actor Watanabe Ken’s long term engagement with communities affected by the disasters. Although many are significantly reduced in numbers they are finding ways to engage in sustainable community development. I so look forward to visiting this area in future.

One more: I fervently recommend the film, Nomadland. Frances McDormand gives an exquisite performance as Fern. After losing her husband and her house, Fern moves into her van and travels the country, working at a series of low-pay, low-respect jobs and finding community with other members of the precariat.

Poem of the Week

Izumi Shikibu was a prolific poet of the 11th century CE in Kyoto. I look forward to reading more of her work some day. Jane Hirshfield translated this little lyric about a house that can no longer be a home.

Although the wind

blows terribly here,

the moonlight also leaks

between the roof planks

of this ruined house.

For Your Reading Radar

British philosopher Melanie Challenger’s How to be Animal has just been published by Penguin in the United States. Challenger takes on the question of our species’ predilection for exceptionalism, and maps out how we might begin to see ourselves as animals again. Stuart Kelly writes in The Scotsman, “(t)his is a provocative, incisive and worried book, carried off with no small degree of élan.”

For Your Calendar

As part of its ongoing Transforming Crisis project, the University of Massachusetts is hosting a conversation on climate change and art between Amitav Ghosh and Emily Raboteau on Monday, April 5th, at 7 PM EST. I am soon planning to write about Ghosh’s The Great Derangement.

The 100% online schedule for the Cambridge (UK) Literary Festival is up, and you might want to check it out. Carys Bray and Jessie Greengrass are hosting a session on their domestic novels of climate anxiety.

That’s it for now. Have a splendid weekend wherever you are! xoxo Nicie