Dear Reader,

The snow is in retreat here, but we are having bouts of bitter cold. There’s a sharpness to the light and a hardness to the look of the ocean.

“There is no frigate like a book to take us lands away” . . . January, especially this January entering the third year of an unrelenting pandemic, is the perfect month for a book that takes you lands away, to a place you probably haven’t been to—or even heard of.

Review

To the Lake: A Balkan Journey of War and Peace

Kapka Kassabova

Graywolf Press, 2020

382 pages

$18.00

This past December 25th marked the 30th anniversary of the dissolution of the Soviet Union. As a slew of new independent nation states emerged, scientists raised the alarm about the normalization of the western border of the Soviet Union. For decades, lands along the edge of the Iron Curtain had been to a large degree restricted from human habitation and access. In this way a unique and ecologically important wildlife corridor had been created, one in which many rare species including the Balkan Lynx appeared to be doing much better than elsewhere. The European Green Belt initiative was formed in 2002 out of a desire to protect this corridor as a resource for wildlife, as a memorial landscape to the history of the Iron Curtain, and as a peace project.

The Green Belt stretches through 24 counties for 12,500 kilometers, from the north of Finland at the edge of the Barents Sea south to Greece and the Aegean. The fact that runs north to south makes it even more valuable in the context of climate change. This initiative is a remarkable collaborative effort to foster biodiversity and sustainable development in some of the least developed parts of Europe, and an example of the necessity for “transboundary cooperation” in the work to preserve the biosphere for future generations.

The southern section of the European Green Belt passes along the shores of Lake Ohrid, which straddles the Albanian border with North Macedonia (formerly The Republic of Macedonia, but recently renamed after a huge fight with Greece). It is to Lake Ohrid that Kapka Kassabova journeys in To the Lake. Ohrid and its sister Lake Prespa, which also borders partly on Greece, are some of the oldest lakes on earth, possibly as much as 10 million years old, and connected by underground rivers along which rare eels and other creatures travel. In the lake bed, archaeologists recently discovered one of the oldest agricultural settlements ever identified in Europe, dating to approximately 5,000 BC. It takes about five minutes on the Internet to understand why humans would have flocked to this region in ancient days to make a life: this has to be one of the most beautiful places that many if not most people have never heard of, and in Kassabova one could not ask for a better guide.

Kapka Kassabova was born in Bulgaria in the early 1970s and emigrated as a teenager with her family to New Zealand, where she attended university. She subsequently moved to Scotland, where she now lives and writes. She began her career as a poet before turning mainly to prose. In Street Without a Name she has written a memoir of her childhood in Sofia, and in Border, a travelogue about the remote and mountainous region where the borders of Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey meet. She has said, “I am drawn to ‘peripheries,’ nexus of cultural confluence and conflict, geographies inner and outer.“

Kassabova is descended from a line of strong-willed, charismatic, complex women, whose lives share patterns of dispossession, separation, and painful illness. Her mother’s mother, Anastassia, grew up in Ohrid. “Somewhere inside her was an abyss that could not be filled. It seemed to have its origins in Macedonia and the Lake. It’s as if she was more than one person, a whole nation of souls, a clamorous hinterland of back-story.” To The Lake is Kassabova’s pilgrimage to this “clamorous hinterland” in search of personal and historical understanding. She seeks out family members and local sages, and explores mosques, monasteries, orchards, islands, and mountains. She tells remarkable stories of resistance, suffering, and survival: of building a secret boat and fleeing for one’s life, of sticking it out through the hardest of times. These are dense, tangled histories, and they are written at length with skill and beauty. Since the book narrates two separate journeys that the author made, you could consider reading the book in two parts.

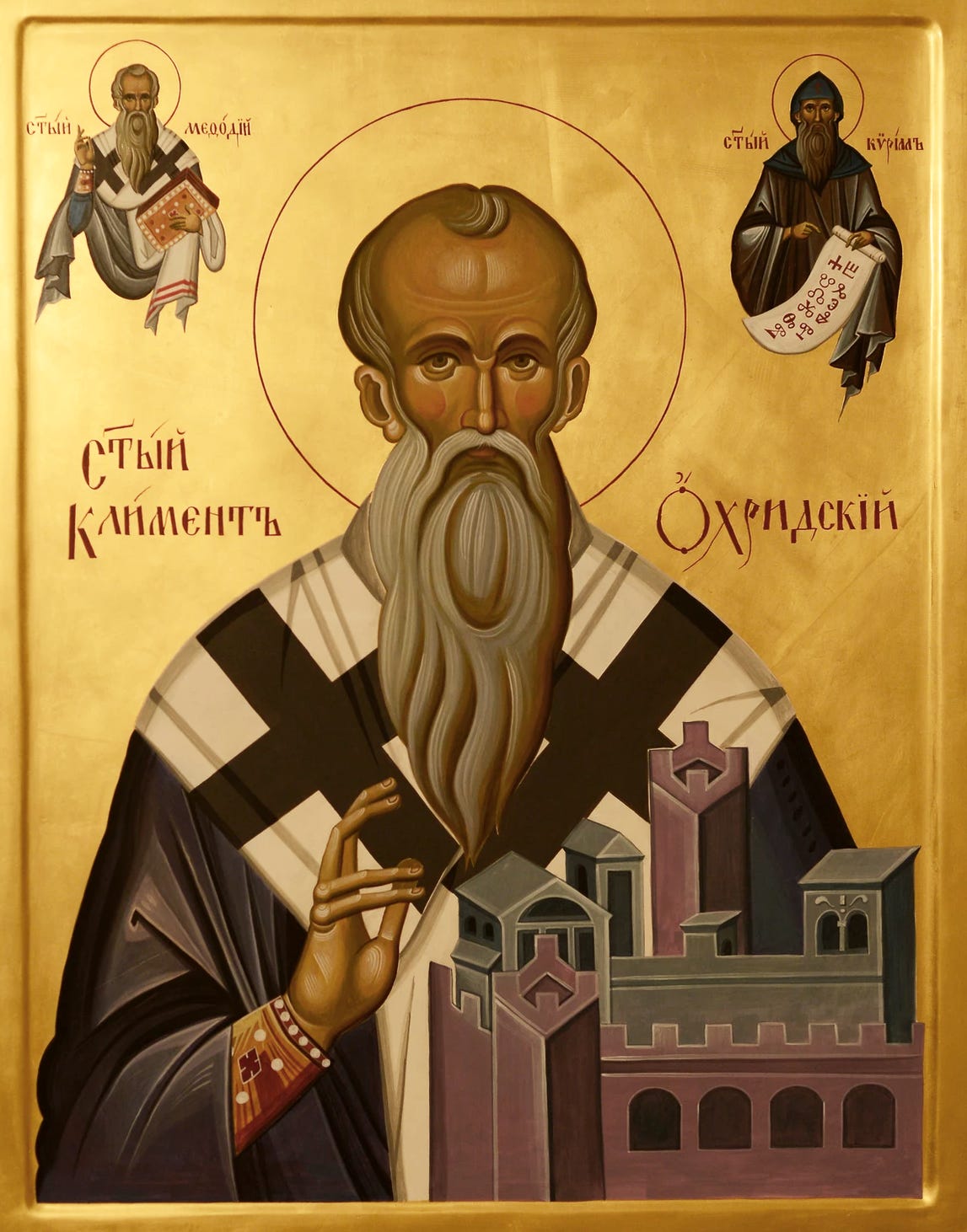

The religious history of this region is fascinating. Muslims and Christians have lived side by side here for centuries, with varying degrees of comity. St. Clement of Ohrid (ca. 840-916) led an intellectual community called the Ohrid Literary School, which consolidated and promulgated Old Church Slavonic and the precursor to Cyrillic script as a common language for the region, all under the reign of Boris I of Bulgaria. He is called the Enlightener of the Slavs, and is entombed in a stunning monastery overlooking the lake.

There are many religious sites around the lakes that draw pilgrims seeking healing. At one in Struga, Kassabova meets a contemporary Clement, nicknamed Clemé, who is working as a keeper of a famous icon, the Black Madonna, as he recovers from a stroke; you can read an excerpt of this chapter on LitHub. The hairpin turns of Clemé’s life story speak to the region’s history of conflict and vengeance, as well as its strong currents of pluralism and toleration. Kassabova clearly has a capacity for acute listening and an eye for the details that illuminate the reality of this remote place.

Women from the surrounding villages brought a loaf of bread, apples from their garden, a few eggs, tied up in festive, embroidered cloths. Women and men with rounded shoulders and children in nylon track suits filed respectfully past the splendidly-robed, cold-eyed priests, who had come down from Skopje. Later they’d collect the gifts and money with their bejewelled hands, distribute it among themselves, pile it up in their expensive cars and drive back to the capital. Like the feudal lords they were — worthy descendants of the patriarchs of Byzantium.

Exploitation and generational trauma are major themes in To The Lake, and as I have continued to read further about Lake Ohrid, it is clear that environmental exploitation of this UNESCO World Heritage Site presents a massive risk. The endemic trout species that is central to the local food culture is in precipitous decline. Unregulated development has led to pollution. Historic buildings have been demolished to make way for cookie-cutter condos, hotels, and short-term rentals.

UNESCO’s recent threat to put the region on its endangered list seems to have sparked some action by local leaders, and there are active NGOs like OhridSOS calling out destructive activities. European Green Belt recently celebrated the mayor of a small town of Kükes, in the highlands on the Albanian side of the lake, for his work on sustainable development and to protect the area’s rare wildlife, such as the Albanian tulip.

As Kapka Kassabova writes, this place, like our whole world, is “[b]roken and fragmented in some ways, eternal and complete in others.” At a time when we need to practice transboundary cooperation to prevent further environmental breakdown, the lake offers itself as a promise of that vision: eternal and complete.

Other Voices, Other Forms

If you haven’t seen it, the lyrical documentary “Honeyland” is available for streaming free on Hulu and for rent on YouTube. In the mountains of Macedonia, a woman cares for her infirm mother and keeps bees using traditional methods. When a new family moves in nearby, everything changes.

Poem of the Week

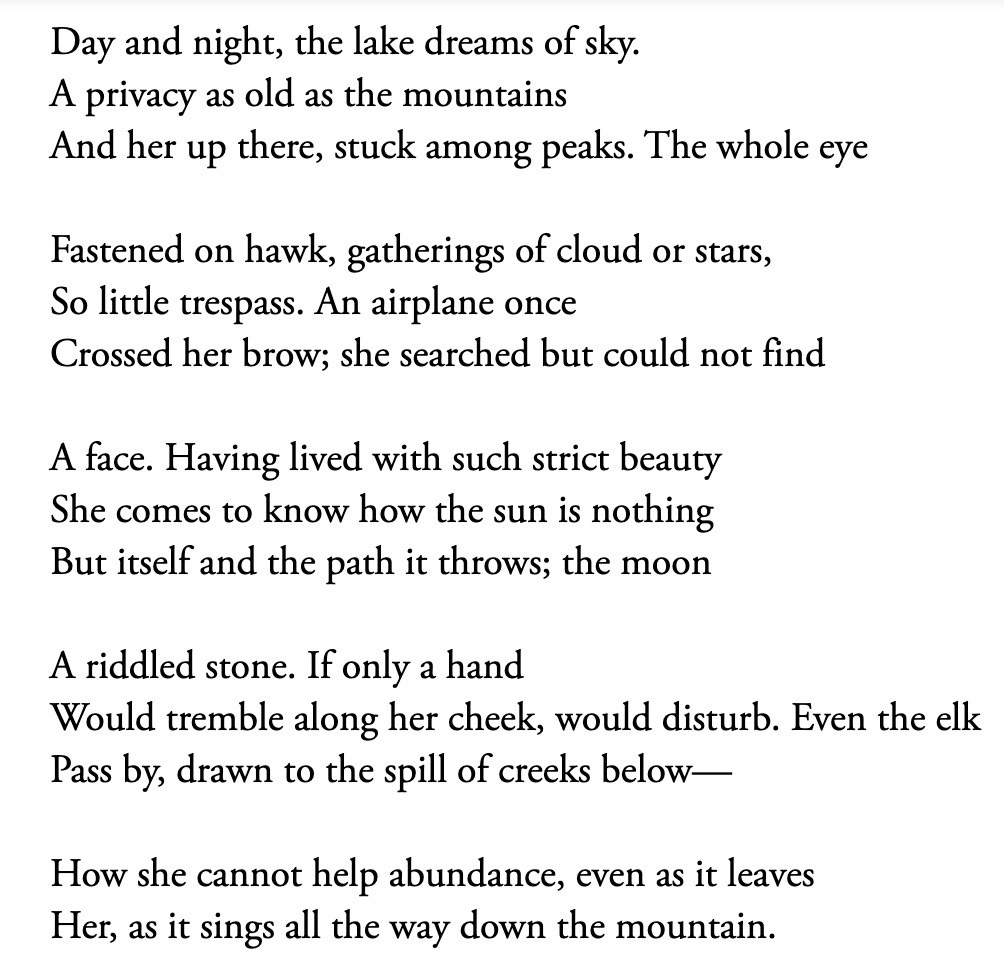

In “The Lake” poet Sophie Cabot Black captures the stillness and “strict beauty” of a lake, the way it becomes an eye.

For Your Reading Radar

My husband kindly gave me The Nature of Oaks by Douglas Tallamy. This gentle account of our ubiquitous neighbors, written by a wildlife ecologist, is full of fascinating lore as well as practical advice for the home gardener.

For Your Calendar

Literature for a Changing Planet is the latest book from Martin Puchner, Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Harvard University, and it couldn’t be more relevant to the Frugal Chariot project. According to the publisher, “Puchner uncovers the ecological thinking behind the idea of world literature since the early nineteenth century, proposes a new way of reading in a warming world, shows how literature can help us recognize our shared humanity, and discusses the possible futures of storytelling.” Puchner will be giving a virtual book talk via the Boston Athenæum this Tuesday, January 18th. More information here.

Bookshop of the Week

Akademska Kniga is one of the leading bookstores in Skopje, Macedonia’s capital.

It is across the street from Skopje’s Church of St. Clement of Ohrid with its extraordinary interior.

That’s all for this week. Take care of yourself. xo Nicie