HAPPY NEW YEAR, Dear Reader!

I begin 2022 with gratitude to all of you for your engagement and support. As you’ll see below, I have plans aplenty for the New Year, and I’m sure that you do also. The comments are open to all, so please chime in with your hopes, dreams, and schemes—anything but weight loss goals! And if you don’t get to them this year, there’s always 2023. In that spirit, I was happy to find a five-year diary from a neat-o Japanese company called Hobonichi. If you give me five years, I can probably get my current to-do list squared away.

Reflections

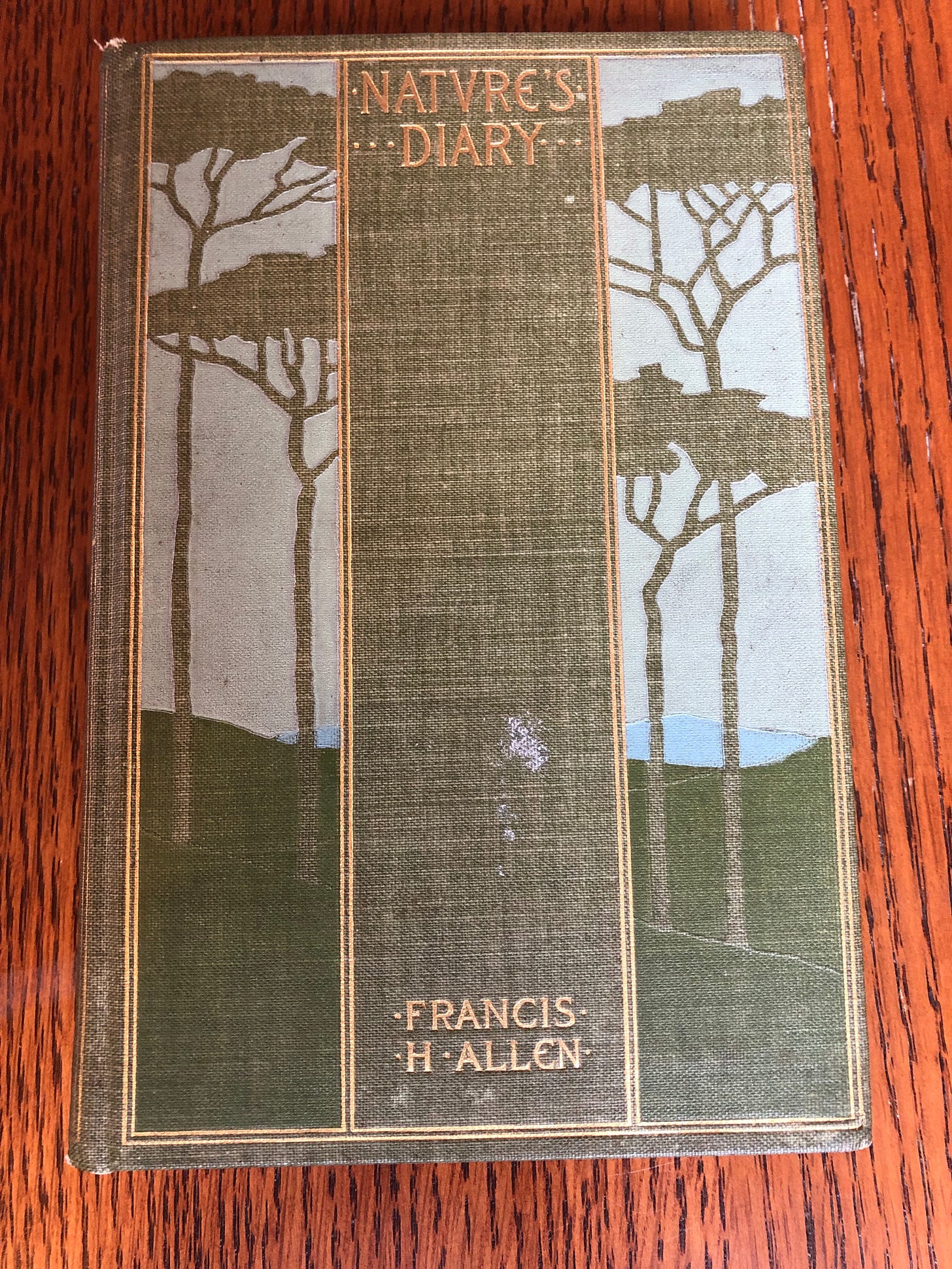

Nature’s Diary

Compiled by Francis H. Allen

Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1897

Unpaginated

It is often said that time is our most valuable resource, and that the gift of time is the most precious thing we can give. But maybe that’s wrong. Or just partial. What if there is a brighter gem: not time, but an understanding of time.

As the door to this strange year falls shut behind us, I think of the moment at the end of Act One of Richard Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier. After a comic flurry of activity that has sent her young paramour into hiding and then into a maid’s costume, the Marschallin, a rich noblewoman at the Viennese court, takes on the role of wise and tender teacher. She foretells that he will leave her one day, sooner or later. This is not what the lover wants to hear, and he protests. Then the Marschallin offers a haunting aria, which begins (in my loose translation of Hugo von Hofsmannthal’s libretto):

Time; it is a strange and wondrous thing.

You can live on and on as if it doesn’t exist, but then suddenly it’s everywhere. It’s all around us; it’s inside us. It creeps onto our faces, it trickles down the mirror, and it flows between my very temples. And between you and me it is also flowing right now, without a sound, like sand in an hourglass.

The Marschallin confesses that sometimes she wakes in a panic in the middle of the night and stops every clock in the house. Then she counsels her suitor:

We must live lightly; with light hearts and light hands we pluck and we taste, we embrace and we let go. Life punishes those who don’t, and God pities them not.

When I first saw this opera performed a number of years ago, I received it as a revelation of middle age. It does seem true that time rushes by as we age, and we become more aware of our mortality. Yet time is more complicated than that. Time is a cultural construct, and it can also speed up and slow down for each of us within a single day. As the physicist Carlos Rovelli observes in his book The Order of Time, “For everything that moves, time passes more slowly.” Perhaps that explains why time seems to stretch out and even suspend itself when we exercise, when we dance, when we concentrate fiercely. Rovelli reminds us that in a world governed by quantum mechanics, our perception of linear time is actually a distortion. “We understand the world in its becoming, not in its being.”

To understand the world in its becoming. Maybe a desire to do just that attracted me to this little book titled Nature’s Diary, as I was browsing this past summer at the mecca known as Shaker Mill Books in West Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Nature’s Diary, long out of print, is a day-by-day guide to the seasonal changes of flora and fauna in New England. It offers quotations from the works of nature writers who were popular at the time of its publication, and it also provides generous space for the owner to make entries. The book was compiled by Francis H. Allen, an executive at Houghton Mifflin and a passionate birder. Allen notes that he leaned heavily on Henry David Thoreau for the daily quotes in the book, on account of his “wonderfully picturesque and epigrammatic style.” Allen went on to write the first Thoreau bibliography, and also edited Thoreau’s journals.

Nature guides, diaries, and calendars were hugely popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This week, book collector John Lehner generously shared with me a few examples from his extensive holdings. The Arts and Crafts movement that deeply informed the designers of these beautiful books developed in concert with the natural and biological sciences after Darwin, and with Romantic and Transcendentalist ideas that celebrated the non-human world.

I may only be the fourth owner of this copy of Nature’s Diary, which was well cared for (and not put to use in the field) by three previous owners, two of whom received it as a gift. The first owner, Anna E. Powell, added only a single entry, on January 21st of 1906: “Heard peepers — very warm!” I smiled a little smile when I read this, because in our time of accelerating climate change, warm days in winter are not only common but are at times experienced with some anxiety. Yet the January thaw was a common enough occurrence in southern New England throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and it was generally welcomed—except by skaters and skiers. I did not smile at the quotation from Burroughs on that same page. “Most of our birds are . . . little changed by civilization.” This is of course no longer true, if it even was then, which I doubt.

In his preface, Allen quotes Emerson’s poem “May-Day,”

Counted on the spacious dial

Yon broidered zodiac girds.

I know the trusty almanac

Of the punctual coming-back

On their due days of the birds.

Allen writes,

These days and hours are not to be reckoned by our own Gregorian calendar; but if we count them on a more spacious dial, we shall find the almanac of the birds and flowers as trusty as Emerson found it.

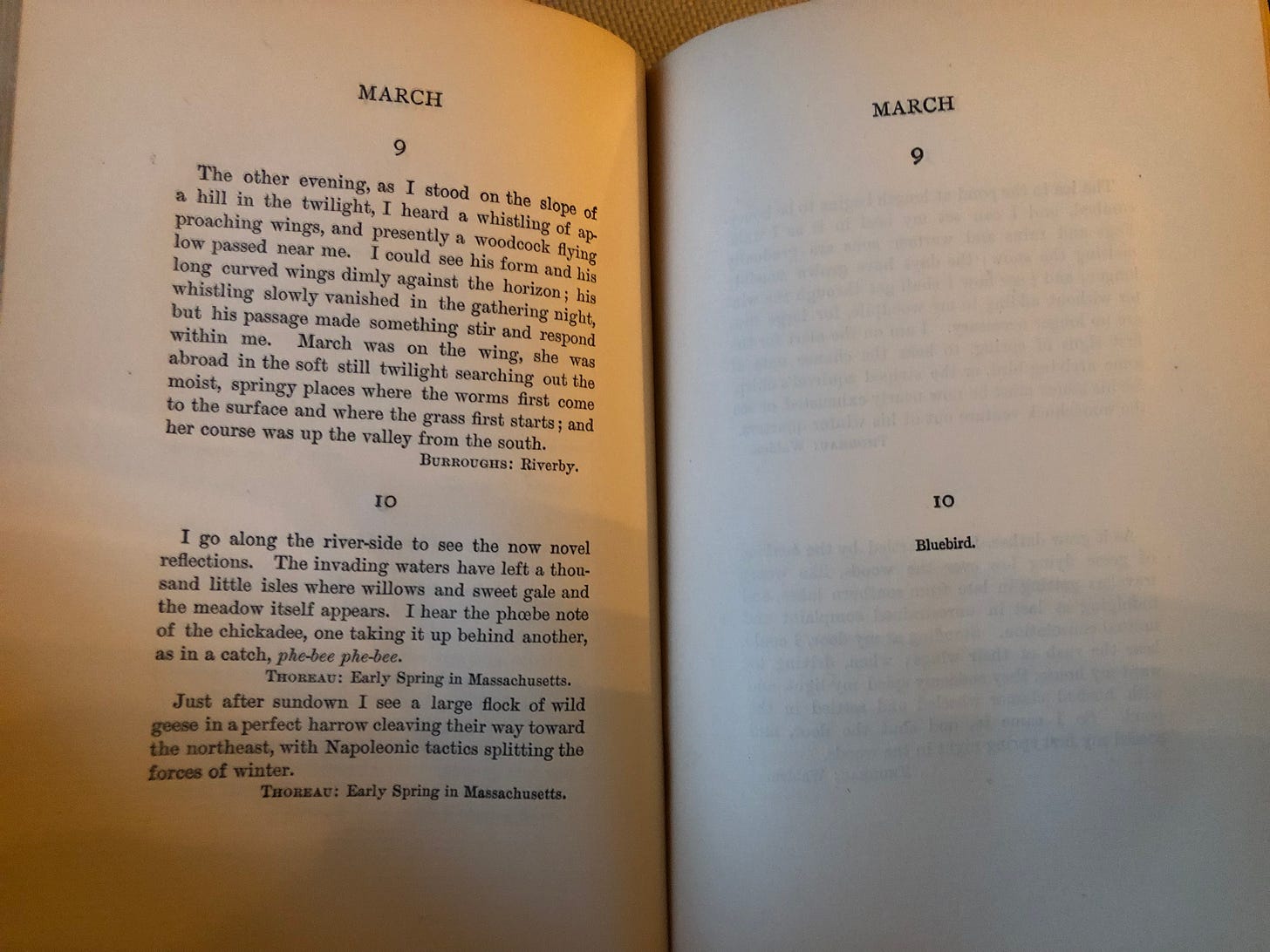

Trusty indeed. We now know that the “broidered zodiac” of the lunar calendar plays a major role in the migration and reproduction habits of many birds. And tide cycles linked to the phases of the moon affect insect behavior in our local salt marshes.

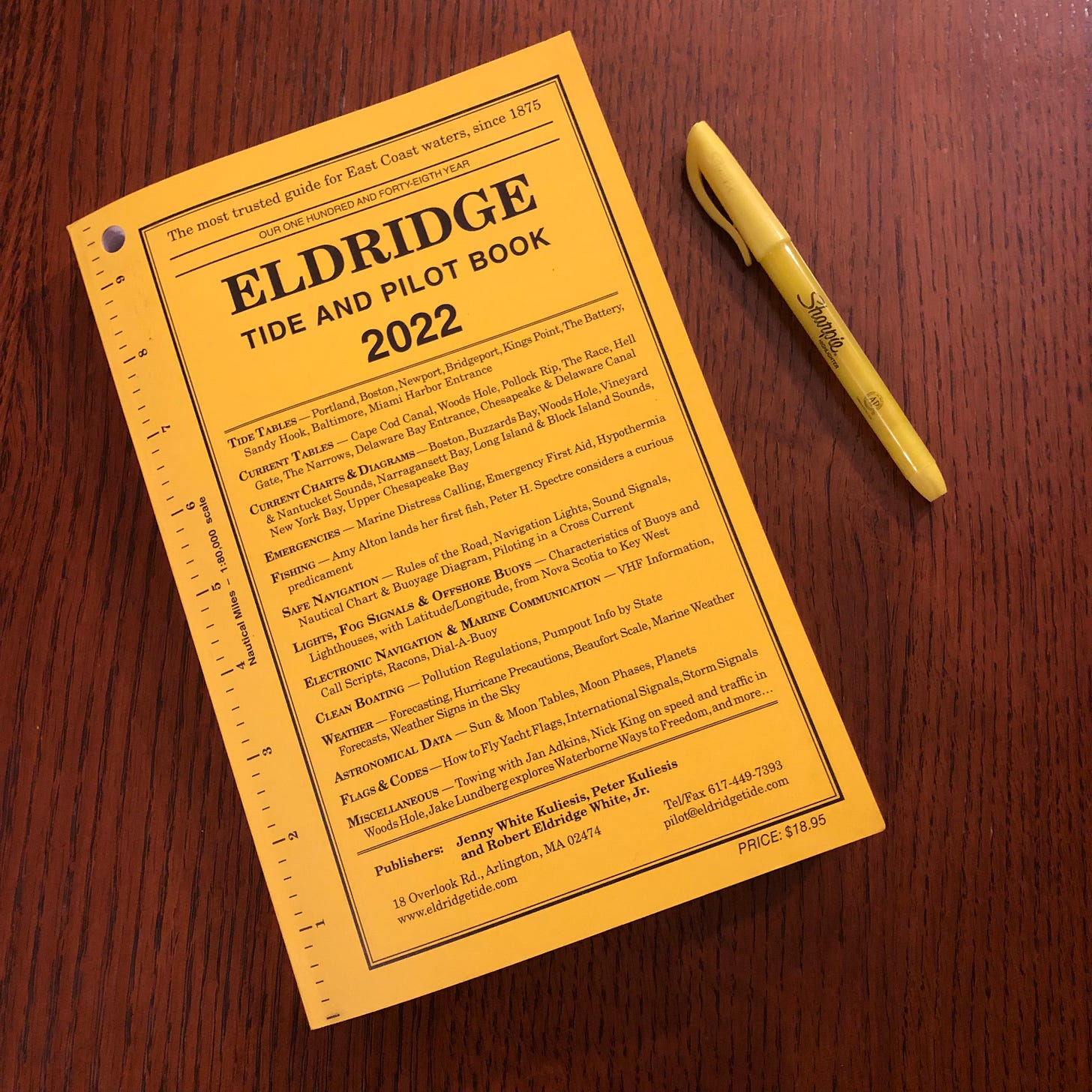

This year, I plan to use the spacious dial of the moon and tide calendars in trying to understand the world in its becoming, at least in a small patch of the world near my home that I love dearly: The Great Marsh. I will be spending time in the marsh ecosystem as often as I can, to observe its beauties and its changes. I have purchased a copy of this year’s edition of the Eldridge Tide and Pilot book, and I plan to organize my explorations around the highest tides, so that I can observe the effects of sea level rise. I also hope to monitor the final phase of a decennial census of threatened saltmarsh birds, overseen by a consortium of dedicated ornithologists. I plan to write about it all.

If you are interested, you can follow this project at a new Instagram account I have created, called @GreatMarshDiary. Here’s the first entry, which provides a time lapse glimpse of one of our more vulnerable local roadways during a recent high tide. As you can readily see, this road is becoming less and less useful, and more and more like a dam we don’t want against waters that won’t wait.

Time is a strange thing, and these are strange times. Bearing witness seems a necessary step, if hardly sufficient. But there is anticipatory delight in wondering when we might see the first bluebird, and whether it will be before or after March 10th—when Francis Allen says I might reasonably expect a sighting of that happy harbinger. Be sure to celebrate your sightings and harbingers. We can’t let go if we don’t first enjoy the embrace.

Other Voices, Other Forms

There are many superb performances of Der Rosenkavalier, and they can be sought out and savored on YouTube and elsewhere. The twenty-first century collaboration between Renée Fleming and Susan Graham is a touchstone, and almost unbearably beautiful.

Poem of the Week

Muriel Rukeyser’s “Elegy in Joy” has a section that seems right for this moment: Nourish beginnings, let us nourish beginnings.

For Your Reading Radar

Echoes from Walden is a new anthology of poems inspired by the life and work of Henry David Thoreau. In a poem called “Letter from Wachusett,” poet Parkman Howe weaves Thoreau’s A Walk to Wachusetts together with a family hike.

In your tent you read Virgil, Wordsworth; you dined on milk and blueberries, for evensong the thrush, her sharp, flute-like pit pit pit. That night the nearly full moon so bright you read "distinctly by moonlight." A fire on Monadnock lit the whole northwest prospect; at home among the community of mountains you felt less solitary; at times you woke to wind roaring over rocks.

The poem concludes

Loss accelerates: war, fire neglect, greed; we are an agitated, impatient people. Even here, deep in the woods, alone on the homeward trail, the leaves hushed and cooling overhead, our boots scuff the mountain gravel loose.

For Your Calendar

Literature Cambridge has planned a Jane Austen Season of Lectures. The first, on “Matchmaking in Emma” with scholar Fred Parker, will stream on January 9th at 6 PM GMT. Details here.

Bookshop of the Week

With all this Thoreau, it has to be the Concord Bookshop, doesn’t it? It looks like they know how to make holiday shopping fun, even in a pandemic.

On to 2022, and see you next week for Silent Earth by Dave Goulson. xo Nicie

It must be in the air! My project for this year is a series of landscape weavings of the seasonal changes of the North River and Daniel Webster property. Following your Great Marsh project now! xx