Dear Reader,

We’re getting extravagantly entangled with fungi this week. But how about this for equinoctial bravura? Behold this giant moth, feeding at the lavish banquet of zinnias over at the barn. According to my Seek app, this is the Bedstraw Hawksmoth, though some friends think it may be a Hummingbird Moth. I believe the latter has clear wings, which this one doesn’t. Let me know if you have an opinion, either via email or in the comments.

Review

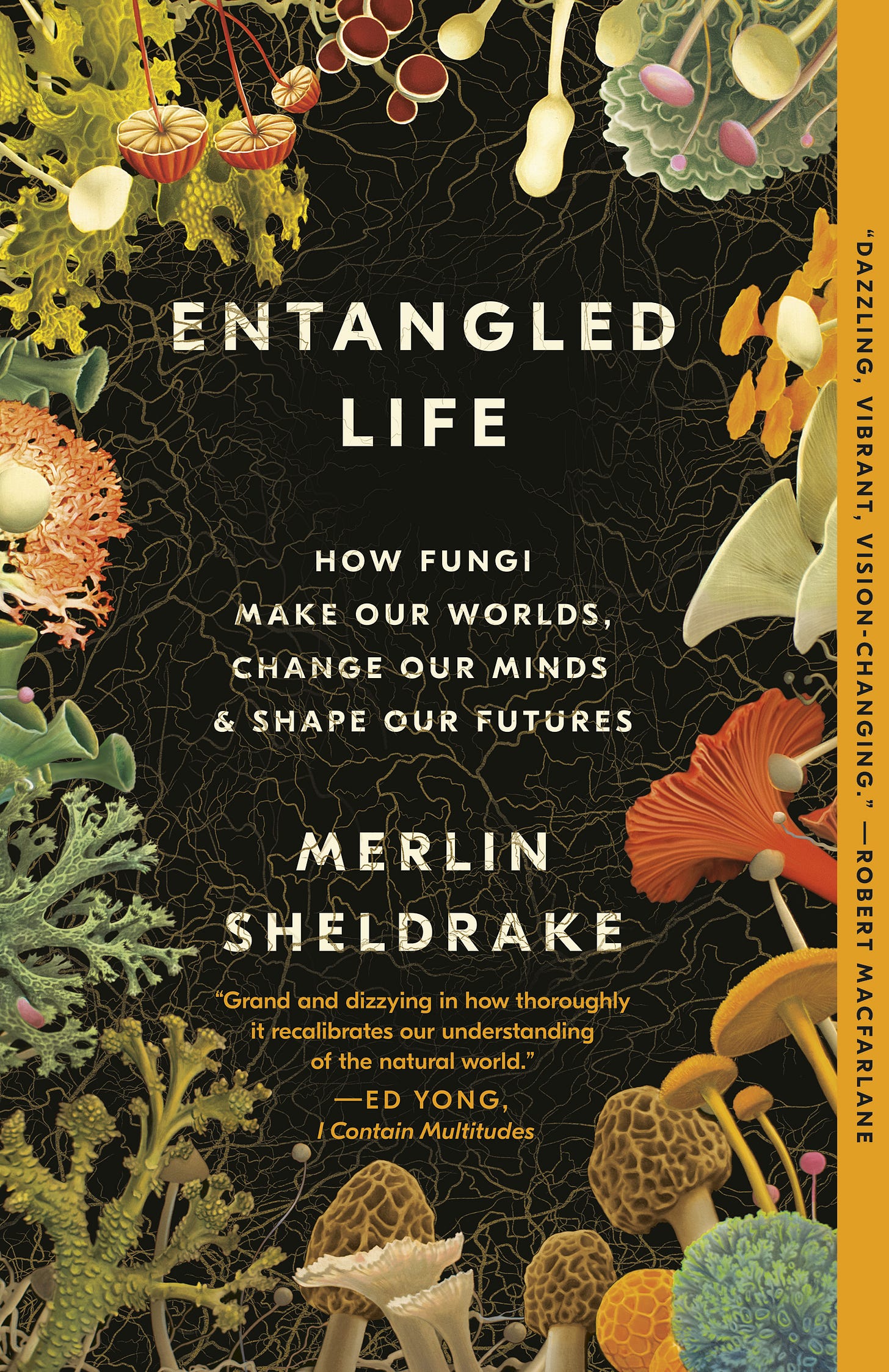

Entangled Life:

How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures

Merlin Sheldrake

Random House, 2020

352 pages

$18.00

“He was given a magical name, and he turned into a magical person,” Robert Macfarlane matter-of-factly asserts in his thumbnail portrait of Merlin Sheldrake. I first “met” Sheldrake in Macfarlane’s splendid Underland: A Deep Time Journey. The two men visit an ancient beech tree and wander through Epping Forest, and Sheldrake tutors Macfarlane on the fungal realm beneath their feet—and around the world. Now, with his book Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures, Merlin Sheldrake, a biologist with a doctorate in tropical ecology from Cambridge University, takes his readers on an epic and extremely enjoyable wander, teaching us about the extraordinary history, diversity, and importance of fungi. There is indeed a magical quality to an author who dedicates his book to fungi, feeds a copy of the book to a fungus, grows oyster mushrooms on the book, and then eats them. Not so much unearthly as ultra-earthly.

Entangled Life begins with its own deep time journey. Sheldrake takes us back five hundred million years, when algae made the transition to dry land only with the help of fungal partners that served as their root systems, until plants eventually developed their own. During the later Devonian Period, spires called Prototaxites, which scientists believe were fungi, grew more than 20 feet tall, and they were the largest forms of life on dry land for forty million years.

Trying to wrap my head around these timescales was strangely cheering. Just as fungi are often the first life forms to emerge after events like wildfires and volcanic eruptions (which devastate nearly all living things), it seems quite likely that fungi will keep on evolving, and inhabiting Earth in the wake of the climate crisis. Fungi will surely help to define the biosphere’s future, whether or not humans become extinct. I had a similar experience when reading Tim Flannery’s Europe: A Natural History, which one of my sisters kindly sent me, and which I also highly recommend. Flannery and Sheldrake are kindred spirits, scientists who season the precision in their writings with considerable ebullience.

Entangled Life makes a convincing case that mycology is one of the most exciting frontiers in scientific research today (one colleague calls it “a neglected megascience”), and that the myriad ways in which fungi and humans interact speak profoundly to the concerns of the Anthropocene. Sheldrake describes the work of researchers who are trying to understand the extraordinary intelligence of mycelial networks, including the ways in which they trace their routes and trade resources with plants, and also how these organisms might relate to neural and computer networks. At the same time, entrepreneurs are developing real-world applications for fungi: to remediate pollution, to combat colony collapse in bees, and to replace plastics. A company called Ecovative has recently developed a novel manufacturing approach. Working with IKEA, for example, their goal is to replace styrofoam packaging with material made from mycelium. The fungus is fed with agricultural waste, including corn stalks and sawdust.

As I read Entangled Life, I thought of Rebecca Gigg’s discussion in Fathoms of the “charismatic” in nature rhetoric. Sheldrake shapes his narrative around the vivid, the quirky, and the downright weird. He goes truffle hunting in Italy, trips on psilocybin, takes a fermentation bath in California, and steals apples from an alleged clone of Isaac Newton’s apple tree to make cider. He also geeks out on the zombie fungi that invade the bodies of ants, control their limbs, and project stalks out of their heads to broadcast spores on neighboring ants—who then become vectors of fungus reproduction.

Perhaps my only reservation about this wonderful book is that fungi are mostly positioned as “good.” Sheldrake doesn’t spend much time considering fungal blights, including the Irish Potato Famine, Dutch elm disease, and the American chestnut blight. Nor does he delve into human fungal infections, which some scientists believe may well be the cause of future pandemics—for which there may be few palliative measures. Valley Fever, for example, is likely to become endemic in broad swaths of the American West. And deadly strains like Candida and Aspergilla could present dire threats to human health.

Some of the quieter, more philosophical sections of Entangled Life will certainly stay with me. Sheldrake meditates on the ways in which fungi and all life forms live in relation to each other, and why the boundaries between species are both necessary and at the same time artificial. If a lichen is the symbiosis of a fungus and a plant, is it actually two different species, or one organism? There is a kind of poetry in the fact that psychedelic mushrooms frequently induce a sense that the boundary of the human self is dissolving.

Sheldrake describes a conference on tropical microbes that made his head spin. In reference to a plant group that had been defined by its production of certain chemicals, it was reported that the compounds were produced within the leaves by a fungus. Then another scientist suggested that these chemicals might in fact be produced by bacteria living inside the fungus. Sheldrake reflects:

Many scientific concepts—from time to chemical bond to genes to species—lack stable definitions but remain helpful categories to think with . . . Our microbial relationships are about as intimate as any can be. Learning more about these associations changes our experience of our own bodies and the places we inhabit. “We” are ecosystems that span boundaries and transgress categories. Our selves emerge from a complex tangle of relationships only now becoming known.

Sheldrake describes a new concept that complements evolution: involution, meaning the ways in which life forms turn constantly toward each other and develop relationships.

Involution is extravagant: By associating with one another, all participants wander outside and beyond their prior limits.

An epic wander, indeed.

Other Voices, Other Forms

I absolutely love the Camden International Film Festival, which presents exciting new work in documentary film each year. Their virtual screenings are winding down this weekend, so jump online and check out the schedule, which offers a number of nature docs. I greatly enjoyed The Mushroom Speaks, directed by Marion Neumann.

Poem of the Week

In this late summer lament, Blackberry Picking, Seamus Heaney speaks to one of our most common fungal interactions: mold on our food.

For Your Reading Radar

Richard Powers, whose tree-centered epic The Overstory was a smash hit, has published a new novel, Bewilderment. Dwight Garner of the New York Times really didn’t like it, not one single bit. But the owner of our local bookshop, Hannah Harlow liked it fine. Hannah says the book is a moving father-son story, an homage to Flowers for Algernon, set in a time of science denialism and democratic backsliding.

For Your Calendar

The Brooklyn Book Festival runs from September 26th to October 4th. On September 30th at 7 PM Eastern, The Center for Fiction is sponsoring a stellar panel in conjunction with Orion Magazine. On America: Environmental Storytelling will include authors Emily Raboteau, Kerri Arsenault, and Garnette Cadogan.

Bookshop of the Week

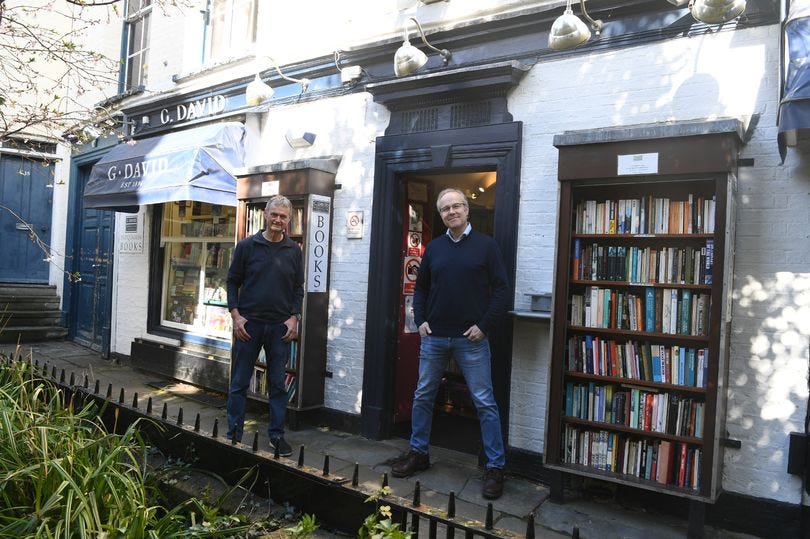

In honor of Merlin Sheldrake, we wander down St. Edward’s Passage to browse for books at G. David, an antiquarian bookshop in Cambridge, UK. The shop, founded in 1896, is co-owned today by the great-grandson of founder Gustave David. It has survived and thrived through two global pandemics. A recent coup was their acquisition of much of the library of Stephen Hawking. I wonder if Merlin or Macfarlane scored any titles.

I will be working on some other projects this week, so I will be back to you October 9th.

xo Nicie