Dear Reader,

Since I wrote last week, we lost our dear one. My aunt Priscilla Johnson McMillan died peacefully, enfolded in the love of given and chosen family. She led an extraordinary and exemplary life and she is profoundly missed. Our thanks to Bryan Marquard at the Boston Globe who has drawn such a fine portrait of Priscilla. Bryan’s work is truly exceptional. He listens, he selects great details, and he structures his pieces not just to highlight what makes someone newsworthy, but to provide the reader a real sense of their humanity.

Priscilla said to me during her final illness “I am always happiest when I am writing.” Which is exactly how I feel. I like to think she would be pleased that I have written something for you even during this sad week. I have a savory summer treat of a book for you, especially for those of you who love the Mediterranean and especially for those of you who think there is nothing so wonderful as messing about in boats.

Review

Lyrical Mischief

Salt Water

Josep Pla

Translated by Peter Bush

Archipelago Books, 2020

454 pages

$20

In Fornells, that fantastically lethargic place, I came to embrace the charms of tedium, Giving time a slower rhythm can be sweeter than honey. Feeling you are alive is to feel you are dying, and awareness of the heart’s ticktock prompts unbearable anguish. In the deep lethargy of a small backwater, that ticktock is barely perceptible. The slightest thing catches your attention and sparks your curiosity.

Embracing the charms of tedium just might be a canny strategy for a writer whose passport has been revoked and who finds himself in internal exile with Fascist censors getting a first look at his prose. Josep Pla (1897-1981) was one of the foremost journalists writing in the Catalan language between the two world wars. As a young writer he fell afoul of the regime. He went through foreign exile, repatriation and a later escape to France during the Spanish Civil War. He returned when Franco consolidated his victory and took power. Pla’s politics were complicated by his Catalan identity and allegiances, but by the ‘40s it was obvious to him that the Franco regime was a disaster, not just for Catalonia but for all of Spain. After World War II, he resumed traveling the world (favoring tankers for transport on which he could write undisturbed) and made extraordinary work about a range of topics. He wrote under a censorship regime for the vast majority of his working years

In Salt Water, Pla seems to be at the reader’s elbow, perhaps with a demitasse of strong coffee in a small café, spooling out tales of the Catalan coast like the warps of the local fishermen. With our rambling guide, we set sail on humble but honest wooden boats for a series of (mis)adventures with a shambling cast of characters like Hermós, who, in velvet breeches and clogs, resembles Dr. Johnson, and drinks a lot of “el roquill. Coffee, cognac, sugar and a few drops of lemon juice.” Come to think of it, the boats might be the most honest characters we encounter. There are wandering minstrels, one-armed mercenaries, and smugglers with names like Fatty Verdera trading in olive oil, spirits, and the occasional gramophone horn. Each story takes its own time, “sweeter than honey,” and ends with “a few drops of lemon juice,” a taste of irony or tragedy that lingers until Pla sets off again and takes us to a new port such as this one.

The afternoon was on the wane, and, as the light dimmed, I was delighted by the whites, blues, ox-blood reds and tawny golds of the stones of Collioure against the dark backdrop of the surrounding countryside, It was a riot of color from an unlikely mix of urban cubes, ancient stone walls, washing hung out to dry and salt-and-pepper trees. All that added to the smell of the sea, the taste of salted fish in the air, the hustle and bustle and messy array of small boats that make for a lively scene. Everything seemed naïve and pungent, a tad wild. . .

What has sealed this volume’s place in the ship’s library of our little sailboat is Pla’s description of a local shipwright building his wooden sailboat Mestral.

Now, small shipyards are a delight. Timber brings a lovely smell. The saw drones monotonously, albeit musically. The tar spitting out from the fire arouses your appetite . . . In winter, the sawdust and wooden chips warm your feet . . . It’s enthralling to see a boat of human proportions being constructed. It requires specialist knowledge — they are true tradesmen . . . Artisans have created the most beautiful, most graceful, most decorous things in this world. What machines make is nasty, horrible, depressing and fatally coarse.

It’s hard not to hear a critique of the militarized and urbanized industrial state in this extended passage, which ends with the following. “You have only to step foot on a boat to see whether the owner is a man of the sea or simply wants to use it to go out and eat a paella once a year with his friends in some corner of a foul-smelling harbor.” Indeed.

Perhaps this is the moment to praise the elegant and zippy translation we have been given by the eminent Peter Bush. Bush relates Pla’s maritime escapades with just the right amount of nautical vocabulary so that the prose feels salty, but still comprehensible to the non-sailor. Pla also uses a lot of adjectives, which can be tricky for contemporary literary readers who have been trained to cut them away from their own prose. But Bush stays faithful to Pla and brings these descriptions off with an élan that is downright emboldening to those of us who do like an adjective or two . . . or three. Some of these tales do meander, but I suggest taking them one at a time. There’s no rush. All honor to the folks at Archipelago Books for their exquisite taste in books and translators.

Salt Water is a pescatarian’s dream, replete with hearty, fishy repasts, generally washed down with bottomless carafes of local wine. There’s a lament for an irreplaceable creator of bouillabaisse. And there are pointed disquisitions on how to preserve anchovies (“ice ruins everything”), and how to cook a lobster (“boiling destroys their divine essence”), as well as how to eat a grilled sardine at sea with your bare hands (like you are “playing the ocarina”). Pla’s description of artisanal netting and trapping techniques (so many special creels) induces pangs of nostalgia for a time when factory ships didn’t threaten to take every last wild fish out of the sea. Pla sees that time, our time, coming.

The signs that point up fishy zones are often known to fishermen via the oldest family traditions, by empirical detail accumulated by their forebears. . . . However, knowledge of all these connections is fading, and will in the end be lost. Human life is being mechanized.

Pla’s world is utterly analog, somewhat anarchic, and extremely appealing. People live simply, feast on the earth’s bounty, hike along creeks from village to village, and rely on each other to get what they need. Institutions are almost invisible and mainly serve to mess things up. As he sails across the border from Spain into France he notes that “No genuine frontier exists between Catalonia and the Rousillon, and that means that a stagey frontier has been created. . . . The centralizing French state quite deliberately emphasized a dialect with the creation of a patois unrelated to the language of the area.” Here again, we see a clever critique ostensibly directed at the French, which could just as well be leveled at the government in Madrid’s efforts to suppress Catalan language and culture.

The book concludes with a series of shipwreck tales, including one involving the father of Catalan artist Salvador Dalí, in which clashing forces and roiling waters beset and imperil human life. Pla confronts the arrogance, ineptitude, and bad luck that bedevil not just sailors, but also, by implication, soldiers and societies. The lyrical mischief of Salt Water, with its quiet undercurrents of irony and fatalism, and Josep Pla’s way of “giving time a slower rhythm” will add savor to a summer day, whether you find yourself on a porch, in a hammock, or snug in a bunk on a humble, but honest boat.

Other Voices, Other Forms

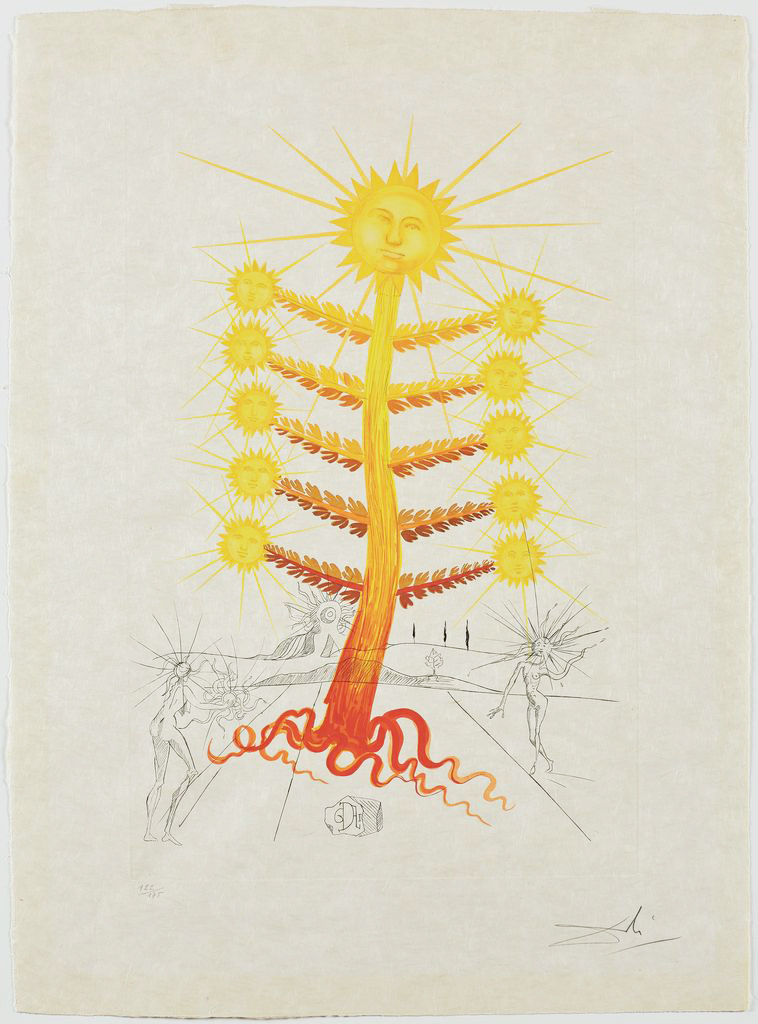

Did you know that Catalan artist Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) made a series of fantastical botanical prints? I didn’t. Some of them are currently on view at the Denver Botanic Garden in a traveling exhibition called Salvador Dalí: Gardens of the Mind, which includes works on paper and Dalí-inspired displays in the gardens. The series, FlorDalí, was made in 1968 in a tribute to the Flower Power movement of the counterculture of the time.

In a review of the show, Robin Lane Fox writes that the series exemplifies his “continuing care, precision, and imaginative wit.”

Poem of the Week

Another Catalan named Salvador was the poet Salvador Espriu (1935-1985), like Dalí a contemporary of Josep Pla. Here is his poem “Beside the Sea” translated by Andrew Kauffman and Sonia Alland.

For Your Reading Radar

You may recall my admiration for the UK publisher Little Toller. They have just released a special collectible edition of Richard Mabey’s important book The Nature Cure in honor of the great man’s 80th birthday. It’s got a stunning color jacket by Michael Kirkman. Mabey made the case bravely for the healing properties of time in the natural world in treating mental illness.

For Your Calendar

Honestly, it’s high summer for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere. We should make Richard Mabey proud and skip Zoom.

Bookstore of the Week

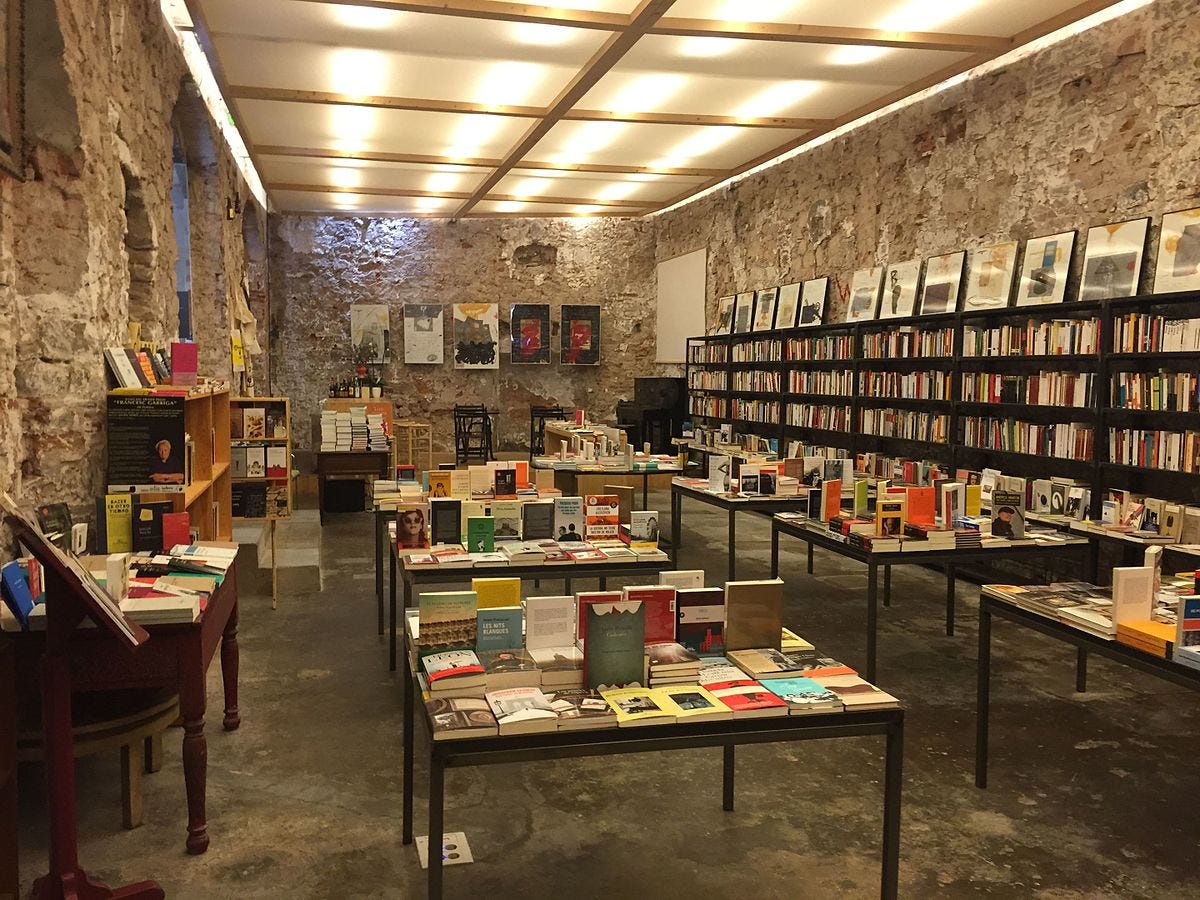

Let’s make a stop in Barcelona on our way to the Costa Brava and pop in to Llibreria Calders, which occupies a former button factory in the Sant Antoni district. It has a piano bar and, according to the Guardian, lots of events after which we can drink refreshing libations under shady plane trees.

Speaking of refreshing Catalan libations, I’m toasting you this weekend with a glass of artisanal vermouth called Muz from Partida Creus in Baix Penedès, the hometown of cellist Pablo Casals. According to my brilliant local wine merchant, Alexis, “Muz is a blend of nearly-forgotten native red grape varietals, fortified with Alpine herbs and citrus.” Whatever is in there, it’s delicious. Here’s to Aunt Priscilla and living right.

Cheers! xo Nicie