Dear Reader,

Welcome to this first issue of Frugal Chariot, your weekly guide to books about nature, climate, journey, and place.

The title of this newsletter comes from a poem by Emily Dickinson:

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing Poetry —

This Traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of Toll —

How frugal is the Chariot

That bears the Human Soul —

A good book is a frugal and infinite vehicle, one that can carry spirits to meet each other across boundaries. I believe that the most important task for humans at this time in the history of our species is to know more deeply our one and only home, Planet Earth. We need to enlarge our understandings of our actions and their effects, but we also need to comprehend better the vast non-human reality that lies beyond our immediate ken: the mysterious glory of what has been and what still exists, of rocks and rooks, stallions and sequoias. If we as humans are to reform our relationship to the more-than-human world, it will be through the power of stories to move our hearts—and inspire us to change our ways.

I am launching Frugal Chariot to share my perspectives on books that I believe bring a particular force of insight and beauty to our time.

I still remember the thrill of learning to read—of shapes on the page suddenly dancing with the music of sound—and I have been a devoted reader for over fifty years. My goal is to help you to discover books you might wish to read, and to provide you with helpful summaries of books for which you might not have the time. I am also hoping to build a node of community for those of us who care deeply about nature writing and place writing.

Each Saturday morning (U.S. Eastern time), I’ll post an essay on a book that I think is worthy of your consideration, along with links to related material. I’ll also be sharing upcoming events that you might want to attend, and forthcoming titles of note for your reading radar. If you are a publisher, publicist, or event organizer, please feel free to contact me with possible listings at nicie.panetta@gmail.com. A companion podcast is also in the works.

Thank you for taking the time to read this inaugural issue. If you enjoy Frugal Chariot, there are two actions you can take:

Click here to subscribe. Paid subscribers can access premium features like discussion threads and online meet-ups. Founding Members will receive personal reading recommendations and undying gratitude.

Tell your people! Share this newsletter with your friends and followers on social media.

And now, on to our first review.

Horizon

Barry Lopez

Vintage Books, 2020

592 pages

$17.00

Is the explorer unavoidably a kind of hunter? The Oxford English Dictionary tells us that “according to ancient authors, the original sense of explōrāre was ‘to scout the hunting area for game by means of shouting.’” In his magisterial final work, Horizon, the writer and explorer Barry Lopez begins by recounting a camping trip to Cape Foulweather near his home in Oregon. A storm is approaching.

The evening of the day before the storm was supposed to arrive at the cape I lay sleepless in my tent, wondering why I returned to the place so regularly, as though one day I expected to find a letter from God. What tugged at me was how well history, biology, geography, quietude, and space came together in this place—at least as I understood these things . . . I’d watch the ancient ocean, watch the infinite variety of its surface, the nap of tweed or sheen of satin or wrinkle of crepe there, losing definition as the evening’s darkening atmosphere settled over it.

He goes on to meditate on the complex life and legacy of his childhood hero, the explorer Captain James Cook. In 1778, Cook made a landfall at Cape Foulweather, his first on the west coast of North America. A storm prevented him from reaching shore, and inspired him to give the cape its name. While Cook’s achievements were profound, his navigational and cartographic accomplishments (“to scout the hunting area”) and his voluminous reports (“by means of shouting”) also enabled conquest and colonization. Whatever his good intentions, his landings could also be understood as having been invasions. Cape Foulweather is a place Lopez has visited many times, and his description is as layered as the landscape is in history. Its name describes not only Cook’s experience with the place, but also our likely future: foul weather.

I felt a particular intimacy at Cape Foulweather with events that were local—the history of the Alseans, the Tillamooks, the Chinook. The differing ecologies of disturbed and undisturbed lands. The summer and winter regimes of light, the neap and spring tides of the lunar months. In some ways I envied Cook the precision and order of his grid of latitude and longitude, the certainty of it, in all weathers and lights, his way to connect one thing directly to another, a deep matrix upon which to lay out a dependable route. But his grid lacked the measure of time.

Horizon is very much a book about time. Lopez looks backward, revisiting the places on Earth that had spoken most powerfully to him about the relationships of humans to each other and to the planet. He takes the reader to some of Earth’s remotest outposts: to research prehistoric Inuit camps in the Arctic, to find turtles living in volcanoes in the Galapagos, to search the Antarctic desert ice for meteorites, to dig for the fossils of human ancestors in Kenya, to understand the history of a penal colony on Tasmania, and to visit Aboriginal communities of Western Australia threatened with ecological and cultural annihilation by industrial resource extraction. This book came at the end of a prolific and brilliant career: Lopez was the author or editor of more than twenty books about humankind’s relationship to the more-than-human world, including the classic Arctic Dreams.

Horizon is also a complex act of reappraisal—of Lopez’s own methods, of his ideas and his ideals. He re-created from his notebooks the journeys that he recounts, even as he was completing his own life’s journey, which ended on Christmas Day of 2020. As the publisher John Mitchinson noted recently, not every writer of Lopez’s stature has the opportunity to craft such a summa statement, and Lopez clearly summoned all his powers. According to his agent, Barry Matson, “He had an ethical, almost religious relationship to the work, a ferocious respect for clarity, for making oneself understood. Many drafts were required: four or five routinely. Horizon required seven . . .” Indeed, ethical is the word that perhaps most readily comes to mind when I think of Barry Lopez’s voice.

Lopez explores, but he is the farthest thing from a swashbuckler. He makes a practice of considering what he might have done wrong: playing a Beethoven tape in a prehistoric Inuit dwelling, taking home small objects from the landscape as talismans. He revises his tactics. He begins to resist the urge to pocket things. He stops taking notes in certain situations. I’ll mention here that Horizon is marketed by its publisher in the “Travel” category. Mass tourism to remote places—what the journalist Scott Carrier calls industrial recreation—can increase pressure on sensitive ecosystems and cultural resources. It is also a source of nonessential carbon emissions, and should be undertaken only with thoughtful consideration. In reflecting on his own role, Lopez offers this caution:

The fact that I haven’t taken anyone’s life, haven’t set up a business that took advantage of people’s naïveté, haven’t seduced them with intoxicants or attempted to enlighten anyone about the strengths of my religion, all seem somewhat beside the point . . . Often it’s no more than this: the white guest does not see himself as a guest. He sees himself as an emissary. Even if he sees himself as only a well-intentioned visitor, he’s prone to believe that, in the long run, he knows best, whether it’s how to sharpen a knife, how to run a bodega, or how to worship the Divine.

Before we can become good ancestors, we must learn to be better guests.

But Horizon is much more than reflection. Barry Lopez also clearly used this book as an opportunity to look toward a future freighted with dread of climate disaster, and to offer what guidance he could before he left life. His was a syncretic vision for H. sapiens. For example, he hoped that we might be able to make common cause with wisdom keepers from indigenous cultures to help us in our wayfinding.

With the indigene’s acute awareness of the depth and intricacy of the local, the myriad relationships that, attended to, create the sustaining wholeness of his immediate world, and with a visionary’s awareness of a fabric comprised of all these local universes, more options for humanity become apparent.

The viability of this vision is admittedly uncertain in his telling, for the reality he documents of human atrocities against the land, against other species, and against fellow humans presses in. After a stirring depiction of his efforts with a local guide in the Galapagos to save sea lions caught in fishing nets, he reports that on his next trip to the area he “saw the carcasses of thirty or forty finless sharks cast up like driftwood on a dozen beaches. The fishermen’s practice was to throw them overboard and leave them to die after cutting off their fins.” The story of his visit to the former penal colony at Port Arthur, Tasmania leaves the reader haunted by man’s capacity, right up to the present day, to perpetrate and justify mass cruelty. The abominable desecration of petroglyphs in Australia to make way for vast mining operations makes one wonder what hope there really is that capitalism can be reformed in time to avert catastrophe.

And yet there is still so much to behold—and hold in the mind—with wonder. If there is a singular pleasure in reading Lopez, it is his capacity, developed and refined over decades, to conjure the numinous three-dimensional happenings of this world on a flat page. As our days are dominated by endless hours on flat screens, our necks bent downward, this is a practice of attention and description that we might all do well to cultivate, even if we never come near to the master’s level of skill. Here’s one scene from a day in the Karijini National Park in northwest Australia.

We swam in still pools of cool water and in slow-moving rivers in the bottoms of several of the gorges, out of the direct rays of the sun but with the brightness of its incident light ricocheting off the walls of two-billion-year-old rick, walls in every shade of purple one might catalog, from damson to heliotrope, from hyacinth to raisin, each purple changing hue as the hours passed and as the sun’s reflected rays became direct, creating a harsher light.

In one canyon we hiked into, we stopped for a while where a narrow river bar had formed and several river red gums and weeping paperbarks had taken root. Jeweled geckos ran the vertical walls on either side of the canyon, great slabs of incinerated blacks and bronzed purples. As I lay back on cool, sandy soil, a flock of about twenty zebra finches passed across the narrow strip of blue above the canyon, small brightly colored passerines with large bills and barred tails, quick as a school of mackerel. They were gone before their wooting cries reached the floor of the canyon where we lay.

There are perfect paragraphs like these on nearly every page. Even the end notes are revelatory.

As good as he was at it, Lopez never stopped considering whether there might be other ways of seeing. Traveling with a group of indigenous men near Uluru (also known as Ayers Rock), he realizes that his very superpower in framing scenes for the reader might itself be a kind of limitation: “. . . they were not as eager to find and hold this two-dimensional view, the one I was most comfortable with, as I was to learn how to stay with them in the realm of three-dimensional, once I located it. The possibility of being able to see a country more fully in this way was clear.”

In the wake of Lopez’s death, there has been an outpouring of tributes. Many have cited these words of his: “If I have a subject, it is justice. And the rediscovery of the manifold ways in which our lives can be shaped by the recovery of a sense of reverence for life.” One searches for a way to capture the injustice that Lopez’s home, near his beloved McKenzie River, was destroyed by wildfire in September of 2020. He lived out his final days as a climate disaster refugee. But then again, it is Lopez who writes, in Horizon: “The world outside the self is indifferent to the fate of the self.” The natural forces we have unleashed with carbon emissions will be indiscriminate.

This is a big, dense, wild, and head-filling book, a tight weave of science, beauty, adventure and philosophy. If you would like a shorter introduction to Lopez’s work, you could turn first to his profound essay collection About This Life. But, Dear Reader, I say take the plunge—either with Horizon or with his other great masterpiece, Arctic Dreams. Once you have adapted to the intricacy of his thought and prose, you may (like me) be ready to let him be your guide—not necessarily to traveling, but to living where we are. Wherever we are, we can try to follow Barry Lopez’s ethical intelligence to the necessary horizon, a future in which humans hunt less and nurture more.

I’d like to end this first review with acknowledgements, a dedication, and from Barry Lopez, a valediction. In a reading life, great books lead on to other books, but so very often it is great readers who first send you on your way. It was from Stephen Sparks that I learned about Robert MacFarlane’s work, and it was from reading MacFarlane that I learned about Barry Lopez. Stephen owns and runs Point Reyes Books with his wife Molly Parent. I am grateful to Stephen and his team for helping me to discover the books I have so needed over the past several years. Thank you. More recently our beloved local bookstore, The Bookshop of Beverly Farms, has been taken over by Hannah Harlow. Hannah has also been a wonderful source of books, ideas, and advice. When I needed it, she had Horizon in stock and occupying pride of place on her Nature shelf. Please buy books from Stephen and Hannah and other independent booksellers!

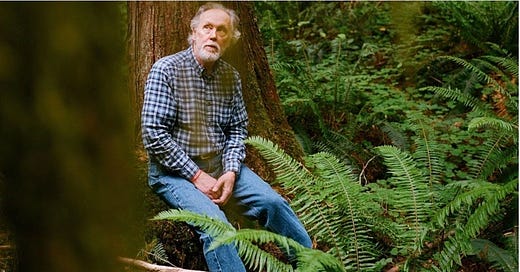

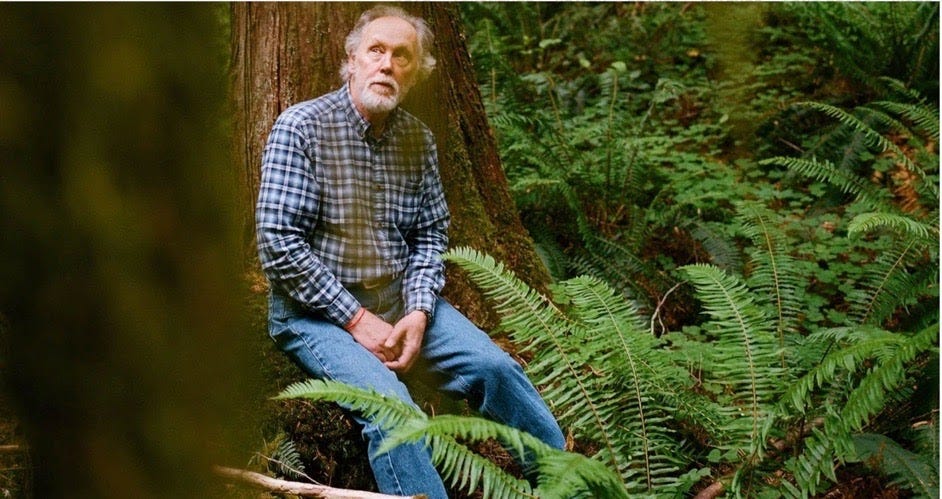

I would also like to acknowledge the brilliant photographer Annie Marie Musselman for graciously permitting me to reproduce two of her portraits of Barry Lopez. They bring his presence to this issue. And I want to sincerely thank my husband, Jay Panetta, for his invaluable assistance with editing and layout, his support of this project, and for making my life one of myriad quotidian joys, even and especially in a pandemic.

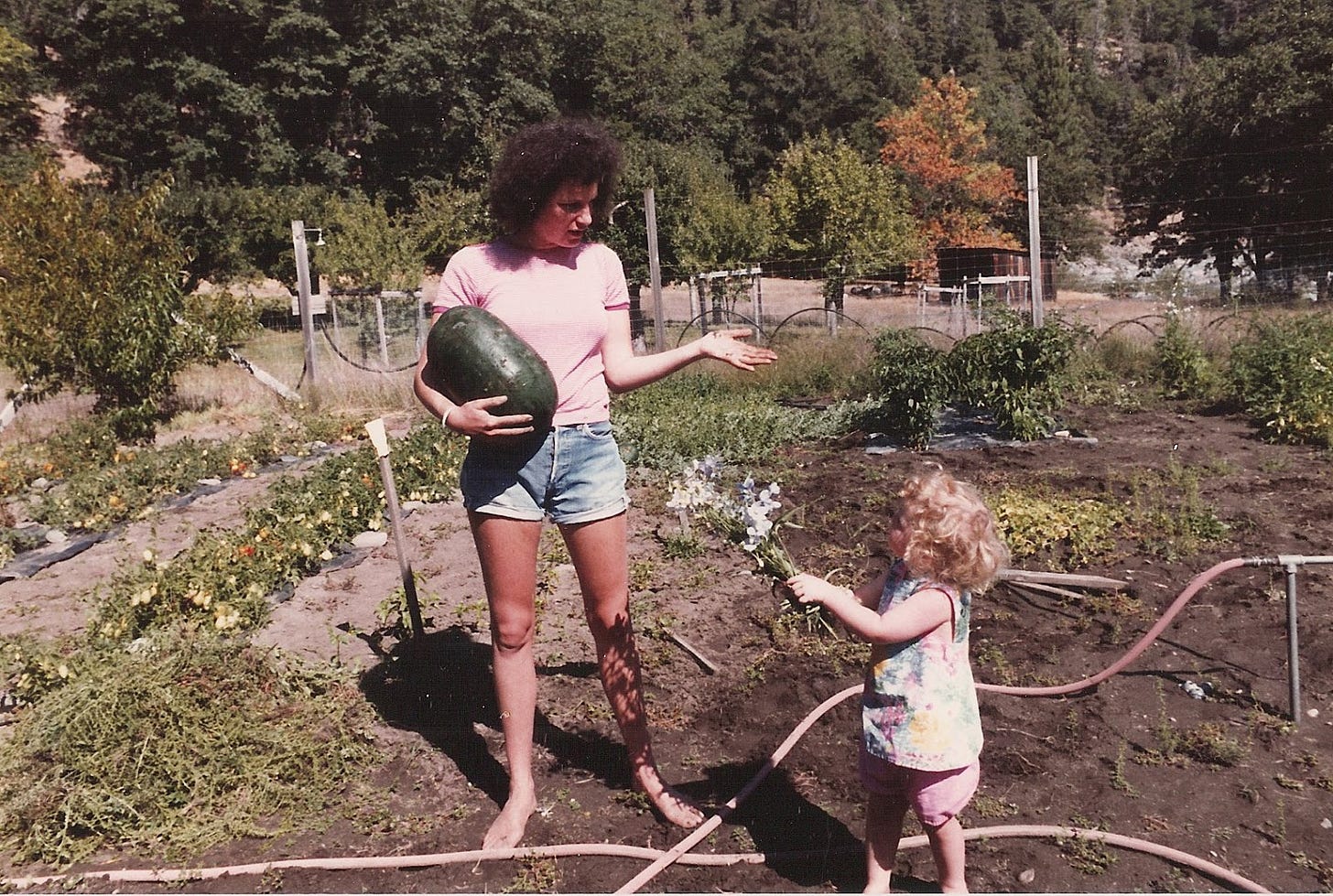

It was a little over two years ago, as I was finishing my last project, that I realized I needed to dedicate more creative energy to the future of our environment. That realization came to me gradually as I spent time in California with my beloved sister Marion Miller, who had become very ill with cancer. Marion was an attorney and environmental activist, and I grew up watching her fight to save the forests and rivers near her home from chemical poisoning and ecosystem destruction by the industrial timber industry. With her husband Jack always at her side, she was fighting not only for her children, but also for the generations she would not live to know. Some of the most joyful and peaceful days of my childhood were spent with Marion, in her lovingly tended vegetable and flower gardens in the foothills of the Trinity Alps. Bounty leapt from the ground under her care. She was a good ancestor. This essay is dedicated to her memory.

Finally, a valediction from Barry Lopez, delivered in 2019 at what was likely his last public reading, sponsored by Point Reyes Books and held at Toby’s Feed Barn in Point Reyes Station, California.

Our job, I think for people my age or maybe a little bit younger, is to help the young people that you see before you shining. Help them find the language they desire, help them tell the stories that they think will cause us to become whole again, to become coherent again instead of incoherent and shattered people. Make common cause with them, take care of them, and we'll be all right, as much as we can be all right. We've got to take care of each other and primarily take care of the young people, my grandchildren and my children. If they can make it and you give them the room in which they can fully imagine what they can see coming, that's not dark. If they can imagine not what is pushing us into the future, but what is calling us into the future. They get that and they can hear that song. They know what is calling them into the future because they're not yet ready to throw it in. And make common cause with them. Give them your love, and let them have your history of learning. They already have the enthusiasm. They have great energy. Give them everything you’ve got.

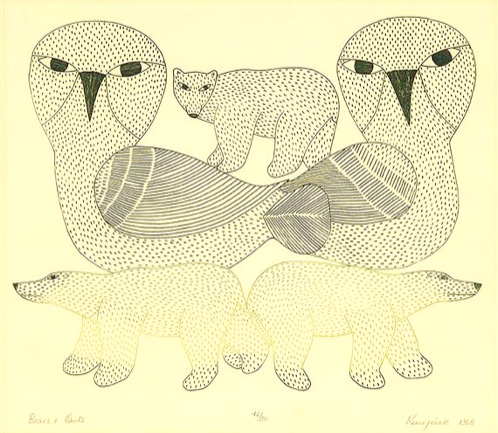

For Your Eyes & Ears: Barry Lopez was an extraordinary emissary to and ambassador for the Arctic. The British Museum mounted a splendid exhibition about the Arctic this winter. The online resources are diverse and wonderful. Special highlights include Magnetic North, a film featuring Indigenous artists of the Arctic, and a talk by the activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier about her work and book, The Right to Be Cold.

Poem of the Week: “My Species” by Jane Hirshfield

One of our great living poets of the more-than-human world, Hirshfield wrote a moving farewell to her friend Barry Lopez, describing him as “A Very Large Array Person.”

For Your Calendar:

Check out the community offerings from Emergence Magazine. They are currently running an online book club read of Arctic Dreams, and their book clubs are beautifully organized. A nature writing class with Chelsea Steinauer Scudder is coming up in April.

For Your Reading Radar:

Elizabeth Kolbert’s latest book, Under a White Sky is just out. Kolbert follows The Sixth Extinction with a deep look at the potential folly of our obsession with technology as a means of salvation.

Have a good weekend, and be sure to get outside if you can. xoxo